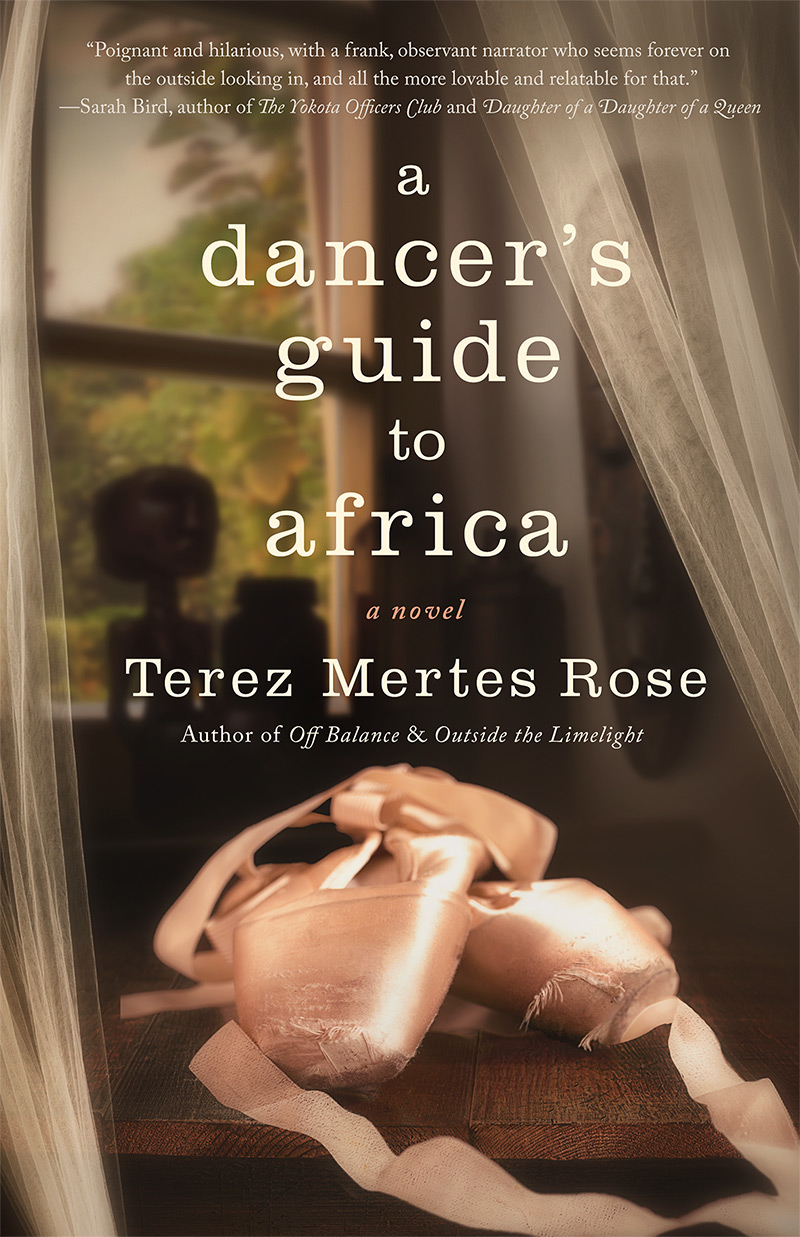

Welcome to Classical Girl’s Africa page! Here you’ll find links and information about Gabon, Central Africa, as it’s portrayed in my novel, A Dancer’s Guide to Africa. Curious about where towns like Makokou, Bitam and Lambaréné — all depicted in the novel — are located in relation to Gabon’s capital city of Libreville? Here you go! Curious how to pronounce words like Makokou (hint: accent is on the first syllable and not the second) and phrases like “case de passage” (kaz de pa SAAGE — rhymes with “massage”)? A glossary and pronunciation guide are forthcoming.

And on the off chance you haven’t read A Dancer’s Guide to Africa yet and chanced upon this page for another reason, well, you can find a link to that book HERE.

Links to educate you

- Click HERE for a 2018 Gabon country profile, courtesy of BBC News

- You’ll find a comprehensive Gabon profile from the site “Countries and their Cultures” HERE

- Click HERE for a 2018 World Bank analysis of Gabon

- Find out what Lonely Planet has to say about Gabon and travel HERE.

An Interview with Dance Advantage’s Leigh Purtill

Here’s some pertinent Q&A from book reviewer Leigh Purtill, who posed these questions after reviewing my book for Dance Advantage.

Leigh Purtill: Fiona, your main character, is a Peace Corps worker in Africa. Did that come from your own experience?

Terez Mertes Rose: It did! Although the circumstances around my joining the Peace Corps were different from Fiona’s. My older brother had served in the Peace Corps six years earlier. I’d thought it was such a dramatic, noble thing to do, and during college years, I set my sights on doing it upon graduation. I was in a dance company through my college years and loved ballet like nothing else, but reality whispered to me that I didn’t have the chops to go professional, and I really had to consider a future outside ballet. I contacted the Peace Corps early on and followed their suggestions on how to make myself an attractive candidate for the job, and it all played out as I’d hoped. It broke my heart to leave ballet and my dance company behind, but it was the right choice.

LP: The book is set in the 80s which is a very specific time and place for our culture. Did you have to do a lot of research to make it authentic? Did you remember everything that was going on then?

TMR: Indeed, I have very specific memories of what it was like to be a Peace Corps volunteer in the 80’s. (My own years were 1985-87; the story takes place 1988-90.) I wanted to keep it in roughly the same time period because conditions change. The AIDS epidemic became a much bigger deal in Africa in the 1990s. There was political unrest in Gabon and its capital city, Libreville, in 1990 (which technically was during Fiona’s time, but I chose not to use any of that in my story – gotta love fiction writing!). Setting the story in 1988 meant fewer logistics errors.

LP: Did you ever consider writing this as a memoir?

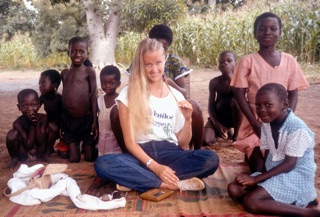

TMR: Nope. My own experiences seemed less glamorous than Fiona’s. I discovered only there in Africa that I was a huge introvert. At my post, I kept to myself probably more than I should have, losing myself in books and writing in my journal a lot. Fiona just flings herself out there and gets into trouble. (Fictionalizing an experience is so much more fun!) Initially I did try to pound out memoir material—I was purely a nonfiction writer at the time—but the end result bored even me. One day I had a “what if…?” moment, created Christophe and this cross-cultural romantic conflict, and wow, did the story take off. The novel just wrote itself, 100,000 words in ten short weeks. It was an amazing experience, just waiting for the right fictional character to show up and make it happen.

LP: Was there material you found difficult to write about? The cultural differences for instance?

TMR: Actually, I loved exploring all the cultural differences through writing. It was a great opportunity for me to process what I’d been too young and naïve to see clearly, back in 1985. (Although Fiona is NOT me, I have to admit that we are very similar in this department.) What I found very difficult to write about was the malevolent character whose intentions toward Fiona were sinister. The penultimate chapter was just awful to work on. Violence repels me. But I think it’s a stronger story for coaxing out that aspect of the culture, because violence exists there, and violence toward women exists there.

LP: Was there anything you left out of the story because you couldn’t find a place for it?

TMR: Tons. Two years’ worth of vivid impressions add up to a lot. I had to pull out an entire story thread that related to AIDS and the way it was just starting to show up in Central Africa in the ‘80s (amid a good deal of official denial in Gabon). And I could have written another novel simply on the political and socio-economic climate of the country. Or tell the story from an environmentalist’s perspective. Or a Peace Corps administrator’s point of view. I have a hunch

there might be a second Africa novel within me. Carmen, Fiona’s best friend in the story, has assured me she’ll stick around and be the narrator for the next one. I might take her up on that.

LP: How do you feel an experience like this in today’s climate might be different from what Fiona experienced in the 80s?

TMR: Great question! I think there is a certainly timeless sense in tradition-bound cultures; I’m inclined to think that in rural Gabon, the locals eat precisely the same thing now that they ate when Fiona was there, which was surely the same thing their grandparents and their grandparents ate in their generation. But the advent of better telecommunications and cell phones and internet would make a HUGE difference. I see blogs online that are composed by Peace Corps volunteers out at their rural posts, and it blows my mind to consider how that would eradicate the feeling of isolation entirely. Getting emails from friends and family? Phone calls any day of the year? Skyping?! I remember reading one volunteer’s comment that “you don’t know real loneliness until you’ve hung up from Skyping with your family.” And I thought, “Um, I knew real loneliness from only speaking to my family four times in a two-year period and that was only when I was in the capital city.” But now that I consider it, maybe it’s even harder for volunteers now, to get this tantalizing glimpse of their own culture, only to have it disappear once the connection ended (or dropped out). Likely, the loneliness blooms anew and you have to battle it all over again. Whereas Fiona, like myself, became immersed in the culture and didn’t leave it until the end of her two-year service. And of course politically, with more democracies in the world – and paradoxically, more unrest, more upheaval as a result – it would be a different experience. I think what is occurring now, as well, is the way educated people from these cultures are starting to question these long-held traditions and superstitions, which serve to harm others (most frequently women). And there are likely an equal amount of people (read: tradition-minded men) who do NOT want anything to change. Fiona was stared at and rudely

questioned for being a single women living on her own in Africa. I think that still would happen, even today.

Want a taste of A Dancer’s Guide to Africa? Here’s the opening scene!

Chapter One

The first thing I noticed was the AK-47, cradled in the arms of the Gabonese military checkpoint guard. That, and the fact that the man looked angry. He sprang to attention as our dust-caked van rolled to a stop, clutching his rifle close, arms at rigid angles. A steel bar, supported by two rusting oil drums, stretched across the unpaved road, preventing us from passing without his permission. Since my arrival in Gabon seventy-two hours prior, part of a group of twenty-six trainees, I’d discovered military checkpoints were common in Africa. At the first one, outside the Gabonese capital of Libreville, the guard had waved us through without rising from his seat. At the second, a soldier was sleeping in a chair tipped against a cinder-block building. Only the noise of our honking had awakened him. But this third official took his job seriously.

Inside the Peace Corps van, I glanced around to see if anyone else noticed the danger we were in. No one was looking. Animated chatter filled the overheated van. “Um, excuse me?” I called out over the din, my voice abnormally high. “Someone with a big gun out there looks very angry.” My seatmate and fellow English-teaching trainee, Carmen, leaned over me to peer out.

“Whoa,” she murmured, “he kind of does. Cool!”

Her fascination shouldn’t have surprised me. Carmen seemed to embrace the gritty, the provocative, evidenced by her multiple piercings, dark spikey hair, heavy eyeliner and combat boots. Although we were the same age, twenty-two, I would have given her a wide berth back home. Here, she’d become my closest friend.

Together we watched the guard draw closer. His eyes glowed with a fanatic’s fervor, as if he were drunk on his own power. Or simply drunk. The authorities here bore little resemblance to the clean-cut police officers back in Omaha who patrolled the suburban neighborhoods, stopping me in my dented Ford Pinto to politely inquire whether I was aware of how fast I’d been driving. That world seemed very far away.

Our van driver, a short, wiry Gabonese man, stepped out of the vehicle and waved official-looking papers at the guard. By the determined shake of the guard’s head after he’d perused them, it clearly wasn’t enough.

The two began a heated discussion. When the driver held up a finger and disappeared back into the van, the guard scowled, tightening his grip on his weapon. Restlessly he scanned the van windows and caught my worried gaze. And held it.

I am going to die. The thought rose in me, pure and clairvoyant.

I pulled away from the window in terror. “He’s staring at me!”

“What are you talking about?” Carmen peered closer out the window.

“No, stop.” I yanked her arm. “I don’t want him to look this way.”

“Fiona. He wasn’t looking at you. He was looking at the group of us.”

“No, he wasn’t,” I insisted. “He was looking for someone to single out.”

Someone to pull from the bus and shoot. The thought, however irrational, made my gut clench in fear.

Carmen studied me quizzically. “You know, they say taking your weekly dose of Aralen gives you weird-assed dreams. Even violent dreams. You didn’t just take your Aralen, did you?”

“No! And are you saying you don’t find this angry military guy with a gun more than a little scary?”

“I do not. I mean, I would if it were just him and me on an empty road at night. But we’re a van full of Peace Corps volunteers and trainees. How sweetly innocent is that? This is Gabon, not Angola. And besides, do you see anyone else in this van getting anxious?”

I glanced around to see if anyone else was bothered by the danger. Conversations had continued without pause. Aside from the occasional idle glance out the window, no one was paying the drama any attention.

“No, I don’t,” I admitted.

Our van driver returned to the checkpoint guard. He said something that made the guard relax his grip on the rifle. He opened one hand and accepted the two packs of cigarettes our driver offered him. Pocketing them, he gestured to a structure adjacent to his building, and the two of them strolled toward it.

“You know, I’m not sure who won,” Carmen said.

I released the breath I’d been holding. “At least he didn’t shoot off his gun.”

Another uniformed guard crunched over to our van. “Descendez,descendez,” he called out in a bored voice.

Carmen and I exchanged worried glances. The volunteers in the van rose, grumbling and stretching.

“What’s going on?” Daniel, another English-teaching trainee, asked, frozen halfway between sitting and standing.

One of the volunteers shrugged. “Checkpoints….”

This wasn’t part of the plan and that concerned me. We were supposed to arrive at our training site in Lambaréné by mid-afternoon. We’d already stopped once for a flat tire and another time for a steamy, bug-infested half-hour, the reason never made clear. No one else seemed bothered by all these delays. Or worried. I could only fret to myself as we descended from the Peace Corps van into the staggering humidity, squinting at the overhead sunlight. Away from the city, deep inside the country’s interior, the whine of insects was a noisy symphony of clicks, buzzes and drones. Jungly trees crowded the landscape, broken only by the red-dirt road and clearing. A group of children, wearing an assortment of ragged thrift-store castoffs, shrieked at our sudden appearance and ran from us. The rifle-toting soldier and our driver had disappeared.

“But what’s the problem?” I quavered, trudging behind the others over to a mud-and-wattle shack set up next to the checkpoint station. “How long will we be here?”

“Who knows?” a volunteer named Rich replied. “Long enough to have a Regab.” He entered the shack and we followed like ducks. In the dim room, lit by sunlight filtering through cracks, Rich pointed to a table where our driver was sitting, relaxed in conversation with the guard. Both clutched wine-sized green bottles of beer. Regab.

To buy the book at Amazon (also available through Ingram and Bookshop Santa Cruz) click HERE.