My return to Africa — if only in my mind — started early one morning last week in the most curious of places: my local classical music station. Something wonderful was playing, a suite of five movements, each one telling its own story in a distinctive musical voice. But who was it? I discerned a hint of Ralph Vaughan Williams. Of Antonin Dvořák ’s New World Symphony. Aaron Copland. Tchaikovsky’s “Souvenir de Florence.” It had a late 19th century feel to it, and yet, a cinematic quality that made it sound contemporary.

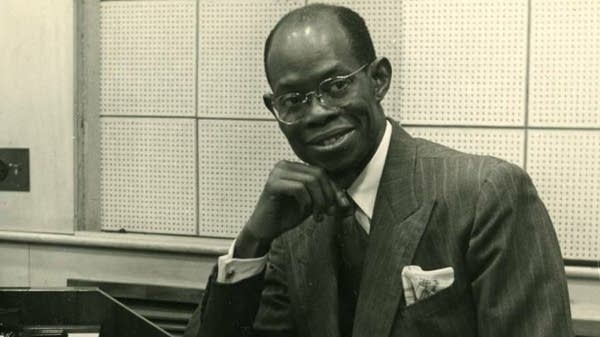

The composer’s name surprised me, in no small part because I’d never heard of him before. But what especially resonated was that he was African: Nigerian composer Fela Sowande (May 29, 1905 – March 13, 1987).

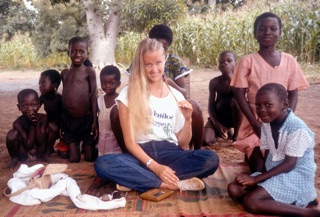

Now if you’re one of my longtime readers, you know how deeply interested I’ve been in Africa since I lived there as a Peace Corps volunteer in the 1980s. And all of you know how enamored I am with classical music. But how many times in my years as The Classical Girl have I been able to mention “Africa” and “classical music” in the same sentence? It thrills me to do so.

Before we go any further, give Sowande’s 1944 “African Suite” a listen. In its five movements, we hear Nigerian musical melodies, harmonies, and rhythms, supported by Western classical orchestration. (Sowande credited Ghanian musician and composer Ephraim Kɔku Amu for the melodies that run through the first and third movements.) Program notes from the Ft. Collins Symphony offer great background information on Fela Sowande and his composition HERE.

You’re probably scratching your head at this point, wondering what African classical music has to do with ibogaine. Here’s how: the morning after hearing the composition, I sat down at the computer to Google Fela Sowande, but an article from The Washington Post caught my eye first. An opinion piece, written by former Texas governor Rick Perry, entitled “I’m dedicating my life to fighting for a psychedelic drug” Here’s an excerpt.

“This month, Texas became the first state in the nation to allocate public funding for FDA-approved clinical trials of ibogaine, committing $50 million, the largest psychedelic research investment ever made by a government. It’s a bold, bipartisan move rooted in science and urgency. Ibogaine is a naturally occurring plant medicine derived from a shrub native to Gabon and surrounding countries in West Africa. It is quite literally a plant root, yet it’s changing the way we think about healing trauma, substance use disorder and brain injury.”

Just like the previous morning’s “African classical music” moment, I felt a shock of recognition and familiarity pass over me. Gabon is the country I lived in during my years in the Peace Corps. Bwiti is a local religion that uses iboga and its derivatives in its ceremonies, particularly the initiation ceremony, in which an initiate is fed bits of the iboga root for hours, to a near-toxic level that allows their minds to transport, traverse, the spiritual realm.

The subject has always fascinated me, and in 2003 as I began writing my first novel, set in Gabon, I dug up everything I could, including interviews with fellow returned Peace Corps volunteers who’d been initiated (shhhhh. That was so forbidden by the Peace Corps and, further, bwiti initiates aren’t supposed to discuss their initiation with outsiders).

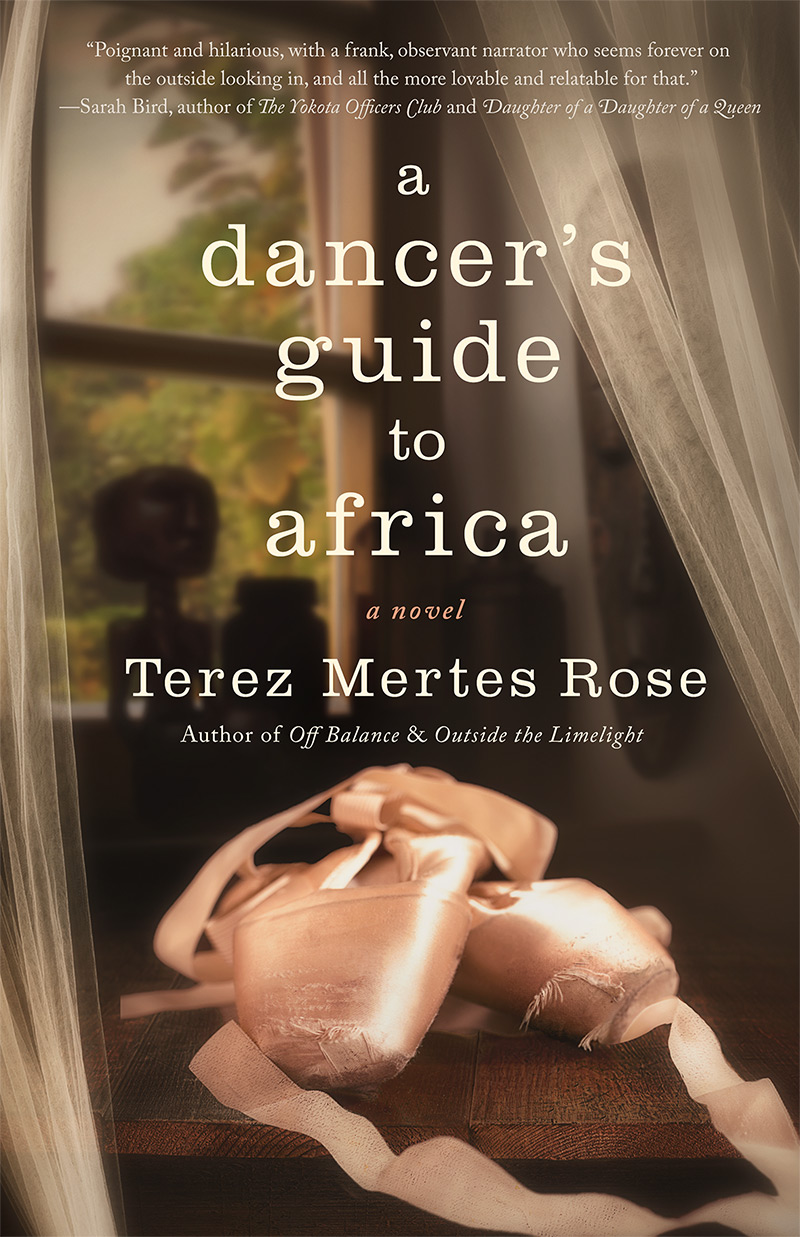

You can find more on the subject, with colorful imagery and interesting details about iboga/ibogaine HERE. But for a more personalized perspective, here’s an excerpt from my novel, A Dancer’s Guide to Africa, where my character Fiona, comically misfit for the experience of two years in Africa, attends a bwiti initiation within weeks of her arrival.

Darkness had fallen, an inky blackness studded with millions of stars. The music began: a percussive clatter of sticks, drums, rattling gourds and the high, strident voices of singing women. The blaze of the bonfire cast shadows behind the villagers as they danced around a man, a bwiti initiate who swayed in a daze. He wore a red pagne—a swathe of fabric—tied around his waist. Red paint had been smeared like a giant cross from his forehead down to his waist and across his shoulders. Two men, bwiti elders, stood close by for support, streaks of chalky white paint punctuating their faces. Around their necks and the necks of the other initiators, hung necklaces composed of feathers, shells and ominous-looking bones I couldn’t categorize.

The bwiti ceremony mesmerized and baffled me in equal parts. It made me uneasy in ways I couldn’t explain, even to myself, as if some energy I’d never before considered had been stirred and now swirled around me like smoke in an enclosed room.

My fellow trainee Joshua and I had spent the past three days in this village, hosted by the community health volunteer who lived here. The trip had been filled with hand-shaking and lots of confusion and smiling, wandering from house to house to shake more hands, sit and listen to the others talk, usually in Fang, the local tribal language here in the Woleu Ntem province. In addition to Regab beer, we’d drunk palm wine, a thin, sour, fermented beverage. Meals had been daunting: rice or baton de manioc topped with a fiery-hot red sauce, sometimes with meat, sometimes not. Manioc, an indigenous tuber, contained cyanide, which meant it had to be soaked in the river or a pond for several days before it was dried, peeled, washed again, then pounded to a pale mush. This was rolled in a banana leaf—the Handi-wrap of Gabon—to form a baton, which got boiled once again. When cut into slices, it looked (and tasted) like those translucent erasers I’d used in grade school.

Bwiti, I’d gleaned, was a local animist religion that utilized the root bark of iboga, a local shrub, to aid in paranormal communication. Joshua, a slim, mild-mannered Seattle native, appeared to know a lot about the ceremony.

“It’s a big deal, a multi-day event. The bwiti elders were probably up with the initiate all last night,” he murmured to me. “I’ll bet they started giving him doses of iboga at dawn, continuing on through the whole day. Look at the way the initiate’s having trouble standing. He is so out of it. Any minute now, they’ll take him into the hut where he’ll lie on a mat and slip into his spiritual journey.”

“Those sticks and roots there are really considered sacred wood?” I pointed to what looked like spring-cleanup yard clippings you’d find in any Omaha backyard.

“Very much so. The root bark is only a stimulant in small amounts, but a hallucinogen in bigger doses. You need a super-big dose for the spiritual journey. I read that the elders give the initiate near-toxic levels, to get him to that place where life hovers close to death.”

I stared at his calm face. “That sounds too creepy. What’s the point—why do people do this?”

“Lots of reasons. Communicate with the ancestors; address infertility issues; maybe discover the answer to some haunting question. Or some of us are just spiritual seekers at heart.”

A man approached and ceremoniously offered us flakes of the iboga. Following Joshua’s lead, I took a piece. It tasted awful, like a wood shaving sprayed with something you might use to kill roaches. I gagged at the terrible bitterness. When no one was looking, I spit it back into my hand.

In the novel, Joshua later goes on to participate in his own initiation. He has a pretty dramatic experience, which Fiona — having plenty of dramatic experiences of her own — coaxes out of him in a searing, transcendent conversation. The e-book is available for FREE right now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble and Apple so there’s never been a better time to check it out. Because ibogaine and its stunning medicinal properties are here to stay, and the world of medicine and healing are all the better for it.

But let’s get back to the subject of Africa-meets-classical music, and two other discoveries I made while working on the above novel. First would be Kronos Quartet’s “Pieces of Africa.” This CD employs the same goal of melding African music with Western classical, but while Fela Sowande’s music sounds distinctly classical, very Ralph Vaughn Williams at times (no coincidence, I discovered, because Sowanda composed it during his years of living in England to depict just that: the experience of being an African in England), Kronos Quartet coaxes out the “Africa” more, courtesy of the music’s contemporary African composers. The end result is fresh, polished, with a distinct classical-meets-Africa sound.

My second discovery was Lambarena: Bach to Africa. Lambaréné is one of Gabon’s bigger cities, and I lived there for my first six weeks in country while training. It features local à capella singers, hurling me right back into my own Africa days, but then, in the same song, it segues into Bach. Pretty singular. You can find it HERE.

There’s so much to say about Fela Sowande, dubbed the father of Nigerian classical music, that I need to give him his own blog in the future. I fell in love with African music while living in Gabon, a love that increased tenfold, years later, as I wrote my African novel. I’ve a hunch that if I read the bios of my favorite two-dozen African musicians (most of whom came from West African and Central African countries), I will discover that they reference Fela Sowande as a source of knowledge and inspiration. Classical composer, scholar, organist, jazz musician, choirmaster, music director, ethnomusicologist, bandleader and more, Fela Sowande was one of a kind.

What a rich and evocative read, Terez! It brings memories of learning about Africa, Gabon in particular, through your letters and later reflections. I once watched a documentary on Gabon during which it was said that certain scholars considered it the actual Garden of Eden.

And the music! So beautiful and visceral, painting the picture of a distant land. I confess my own exposure to African music has been limited to Groove Africa by Putamyo, a genre-spanning collection of contemporary African sounds.

One other moving musical image comes to mind… from the delightfully quirky movie “The Gods Must Be Crazy” which is based in and near the Kalahari Desert. The villagers greet the new white, blonde haired teacher (sound familiar?) in song, all of them coming from the fields, their huts and common places, waving and singing to welcome her. https://youtu.be/ghELvjjOooE?si=s7fkjq4dchCxt-En

I remember too your stories about the omnipresent manioc. Years later, as I delved into google to find how what tapioca came from, I was surprised to learn that the term most often refers to the starch extracted from the cassava root (all that cyanide!😱) while manioc is a common name for the plant itself. Hmmm, now I’m peckish for some tapioca…

Love the reminiscing about your time in the Peace Corps. I vividly remember your writing about the iboga experience. It cracks me up that Rick Perry of all people is promoting this psychedelic treatment drug. Glad it’s getting the exposure it deserves.

Thank you Annette and Kathleen for your comments. I so enjoyed reading them! Now I’m off to click on the link Annette left!

… Returning from watching the video clip. LOL, was THIS what gave me romantic illusions about setting off to Africa to teach the children how to speak English? Meanwhile, my actual arrival at my new post? LOL. Not this. Hardly.

I first discovered Kronos Quartet’s “Pieces of Africa” in college in the early 90’s and listened to it so much. My favorite piece was “Kutambarara” and I still enjoy it. I was fortunate enough to have visited Africa several times for work (at the NIH) and this was always on my playlist, I think I will listen to the whole album again 🙂

Ooh, loved reading your comments, Deborah! Very cool that you were able to visit Africa several times for work. A win-win, as it’s a fascinating culture to observe but costly (and a wee bit dangerous) if you’re a solo traveler just wanting to see the world.