Thanksgiving, when you get down to it, is all about tradition. Year after year, we seek out (or avoid) family and familiar recipes, pull out Grandma’s china, and strive to create the same meal we’ve had every year. Turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie — overeating, too, is part of the tradition.

The variables quickly change, however, when you’re 6000 miles from family, unable to return home for the holidays. Then, homesickness is what cramps your stomach. But perhaps this, too, is part of the tradition.

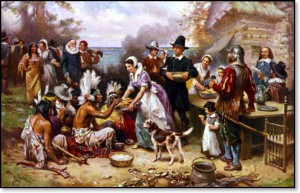

Consider the band of fifty survivors in Plymouth of 1621, who gathered to celebrate their harvest with their newfound native American friends. The Pilgrims-to-be had left extended family and a familiar world behind, and in the course of a year, had lost an alarming fifty percent of their compatriots to sickness. Now that’s a recipe for homesickness.

My first taste of a foreign Thanksgiving came in 1985 when I left my native Kansas for the Peace Corps in Gabon, Central Africa. The early months, amid Gabon’s heat, staggering humidity and unfamiliarity, were the hardest. At my provincial post, where I taught junior high school English, my white skin stuck out like a beacon. Whispers and stares accompanied me everywhere I went. I persevered with a grim determination, teaching, dressing and acting like the American I was.

November brought with it dreams of the upcoming holiday. Back home on the Big Day, Mom would set the table early with linens, her delicate china and fine silverware. The rich smell of slow-roasting turkey would pervade the air as family members congregated throughout the day. Laughter, conversation and the clink of silverware against china would fill the dining room later as ravenous eaters stuffed themselves into a stupor.

Home. So very far away.

The only way to combat the homesickness, I decided, was to host my own traditional Thanksgiving dinner. My announcement to the other Peace Corps Volunteers, however, was met with skepticism.

“Good luck finding the ingredients,” one said.

“Last year we just drank beer,” another offered. “Trust me—it’s the safest bet.”

Perusing the local store brought only further discouragement. No whole turkeys, only the wings (the good parts stayed in the U.S.). No fresh vegetables and no potatoes, only local tubers like manioc, taro and plantains. Not a chance of pumpkin. “Fine,” I snapped to the others at our next meet-up, “no Thanksgiving dinner this year.”

“But why does it have to be a traditional dinner?” a Gabonese friend who’d joined us asked.

“Well that’s the point, to do it the way it’s always been done, with the turkey and stuffing, mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie.”

“Maybe if you compromised, you’d find it easier.”

Compromise. That action, so difficult for us to consider—politically, socially and personally. Why do we resist compromise? Maybe the Pilgrims would have fared better early on, had they compromised in myriad ways. Maybe I, too, would fare better in this foreign country if I tried embracing the culture instead of peddling my own.

The Thanksgiving feast I ended up serving was unlike any I’d had before. It included oven-baked turkey wings, baguette stuffing, mashed taro root and canned French peas. Flour biscuits became dinner rolls. Gravy–forget it; it was too hot outside anyway. For pumpkin pie, I boiled green papayas from the market, spiced them up with cinnamon and nutmeg, then proceeded with the traditional recipe. The guests, both American and Gabonese, were delighted.

“I’ve never had turkey wings cooked this way before,” said one Gabonese man. Another reveled in the concept of biscuits with dinner. I thought back to the first Thanksgiving dinner, where the Pilgrims cooked unfamiliar food with familiar recipes. Maybe a Native American invited to the feast tasted a dish and said, “Hey, I never thought of doing that with corn before.”

When I served the green papaya pie, I watched the other Americans’ expression as they took the first bite, trepidation changing to amazement. “This tastes just like my Mom’s pumpkin pie!” one exclaimed. “How did you do it?”

Tears stung my eyes and at that moment I felt happier than I’d ever felt in Africa, more fulfilled by Thanksgiving dinner. For the first time, I truly gave thanks: for friends, for bounty, for opportunity. And for my newest lesson: the art of compromise. Not a bad addition to a traditional American celebration.