Seems there’s a perennial hunger to explore the personal lives of the globally wealthy, evidenced by the recent blockbuster success of the novel-turned-movie, Crazy Rich Asians. Even as a returned Peace Corps Volunteer, I admit it, I’m not immune. I realized how much that was the case, sixteen years ago, when I started writing The Africa Novel. (My regular readers have heard all about this. If you’re new, go HERE and HERE.) The writing stalled; it seemed bland, more earnest than exciting, until a character and a situation sprang to mind. How about, I mused, instead the stereotyped altruistic, liberal-minded, upper-middle-class American girl helping those less privileged, I’d make her humbler. Bumbling. And the main African character, Christophe, would be a wealthy, privileged, pampered African, far more cosmopolitan and privileged than narrator Fiona. It’s not that big of a stretch, either. Every country has its elite, and trust me, this includes African countries. Building on this, I made Fiona a cloistered Midwesterner girl from a good family, but a modest, middle-class one. A ballet dancer, at that, more “save the pointe shoes” than “save the world.” The main reason she joined the Peace Corps was to get far away from her sister’s bitter betrayal. Running from conflict, she landed with a thud in Gabon, Central Africa, where her encounters with the wealthy, charismatic (did we mention sexy and good looking?) Christophe leaves no doubt that conflict will continue in her life. Fiona, over the course of the next two years, is in for an education. Then again, so is Christophe.

Mind you, A Dancer’s Guide to Africa has more depth than “impressionable Midwesterner falls under the spell of wealthy, sexy African man.” Alongside Fiona’s desperate infatuation is the struggle to acclimate in this world so wildly different from the one she grew up in. Her American precepts of being a “fun” English teacher, and being an outspoken, assertive female, land her into trouble, time and time again. In a country where family is everything and children are wealth, the single, unattached Fiona is considered poor beyond measure. And then there’s Christophe, his family’s fortune, their mansion, their ocean-front, palm-fringed vacation villa. While he and his family are purely fabrications of my imagination, I’m certain they represent a segment of Gabon’s population. Gabon enjoys a per capita income four times that of most sub-Saharan African nations. (Think: oil, the fifth largest oil producer in Africa. And manganese and lumber and other natural resources.) But there is a high income inequality, and a large proportion of the population remains poor. And the rich—well, many of them are crazy rich.

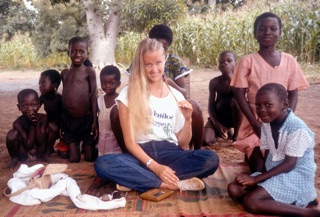

I’ve been asked, in interviews, what I’d like readers to take away from A Dancer’s Guide to Africa. There’s the obvious: I want readers to enjoy a good yarn, with dance but not too much; with romance and conflict, but not too much. But beyond that, I wrote this story to share with armchair adventurers, incorporating the grit of Africa, the unforeseen challenges, the bafflement and reverence, in the hopes that they come to “see” the Africa I saw. In some ways I wrote this as a love letter to Africa, one that I want to share with the world. The more all people can relate to or simply learn about foreign cultures, understand them at the personal level, the better this world will be. There are rich Africans, here and abroad. There are poor, under-served, struggling communities right here in the U.S. Values can vary wildly between cultures. Life isn’t fair, for so many people. There’s so much suffering in one part of the world, so much entitlement in another part. Fortunately, the hunger to connect, find affiliation and love, seems to define us all. I hope we take that similarity, that yearning for connection, and instead of saving the world, maybe just save each other.

You can find A Dancer’s Guide to Africa HERE or through Bookshop Santa Cruz.