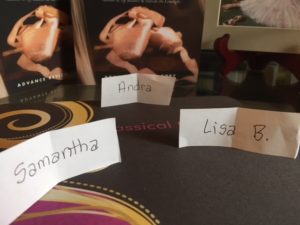

Thank you to all of you who entered my giveaway drawing for Amazon gift cards and advance reader copies of A DANCER’S GUIDE TO AFRICA. I’m happy to announce the following:

First prize

A $25 gift card from Amazon and a print copy of A DANCER’S GUIDE TO AFRICA, goes to… Andra!

Runners up

A $5 gift card from Amazon and an electronic copy of A DANCER’S GUIDE TO AFRICA, go to… Lisa Blanchard and Samantha!

Congratulations, winners! I will be contacting you via the emails affiliated with the comment posted (or if you emailed me directly). If you don’t hear from me by the end of the week (because tomorrow is the 4th of July and I ain’t working!), please do contact me! If you have an AOL email account, they can be notorious for deciding that the Classical Girl admin email address is spam. Boo hoo, AOL!

And for the rest of you, thank you so much for contacting me and adding your name to the bowl. If any of you would be interested in being an advance reader and posting a review of the book on Amazon once it’s published (Oct 2nd), I will be making the novel available to all reviewers on August 2nd. It will be available through NetGalley, but if you’d like me to contact you and send you a reviewer’s copy privately, I’d be happy to do that. Just let me know, either in comments below, or via email.

Thanks, all, for celebrating my 200th post, and I look forward to celebrating with you all again, in three months’ time, when A DANCER’S GUIDE TO AFRICA gets released into the world!

Want a taste of what’s to come on October 2nd? Here’s the opening chapter from A DANCER’S GUIDE TO AFRICA. Note that WordPress has squished some of the words together. If you prefer the better formatted version, click on this link: Chapter 1, A Dancer’s Guide to Africa

Chapter 1

The first thing I noticed was the AK-47, cradled in the arms of the Gabonese military checkpoint guard. That, and the fact that the man looked angry. He sprang to attention as our dust-caked van rolled to a stop, clutching his rifle close, arms at rigid angles. A steel bar, supported by two rusting oil drums, stretched across the unpaved road, preventing us from passing without his permission. Since my arrival in Gabon seventy-two hours prior, part of a group of twenty-six trainees, I’d discovered military checkpoints were common in Africa. At the first one, outside the Gabonese capital of Libreville, the guard had waved us through without rising from his seat. At the second, a soldier was sleeping in a chair tipped against a cinder-block building. Only the noise of our honking had awakened him. But this third official took his job seriously.

Inside the Peace Corps van, I glanced around to see if anyone else noticed the danger we were in. No one was looking. Animated chatter filled the overheated van. “Um, excuse me?” I called out over the din, my voice abnormally high. “Someone with a big gun out there looks very angry.” My seatmate and fellow English-teaching trainee, Carmen, leaned over me to peer out.

“Whoa,” she murmured, “he kind of does. Cool!”

Her fascination shouldn’t have surprised me. Carmen seemed to embrace the gritty, the provocative, evidenced by her multiple piercings, dark spikey hair, heavy eyeliner and combat boots. Although we were the same age, twenty-two, I would have given her a wide berth back home. Here, she’d become my closest friend.

Together we watched the guard draw closer. His eyes glowed with a fanatic’s fervor, as if he were drunk on his own power. Or simply drunk. The authorities herebore little resemblance to the clean-cut police officers back in Omaha who patrolled the suburban neighborhoods, stopping me in my dented Ford Pinto to politely inquire whether I was aware of how fast I’d been driving. That world seemed very far away.

Our van driver, a short, wiry Gabonese man, stepped out of the vehicle and waved official-looking papers at the guard. By the determined shake of the guard’s head after he’d perused them, it clearly wasn’t enough.

The two began a heated discussion. When the driver held up a finger and disappeared back into the van, the guard scowled, tightening his grip on his weapon. Restlessly he scanned the van windows and caught my worried gaze. And held it.

I am going to die. The thought rose in me, pure and clairvoyant.

I pulled away from the window in terror. “He’s staring at me!”

“What are you talking about?” Carmen peered closer out the window.

“No, stop.” I yanked her arm. “I don’t want him to look this way.”

“Fiona. He wasn’t looking at you. He was looking at the group of us.”

“No, he wasn’t,” I insisted. “He was looking for someone to single out.”

Someone to pull from the bus and shoot. The thought, however irrational, made my gut clench in fear.

Carmen studied me quizzically. “You know, they say taking your weekly dose of Aralen gives you weird-assed dreams. Even violent dreams. You didn’t just take your Aralen, did you?”

“No! And are you saying you don’t find this angry military guy with a gun more than a little scary?”

“I do not. I mean, I would if it were just him and me on an empty road at night. But we’re a van full of Peace Corps volunteers and trainees. How sweetly innocent is that? This is Gabon, not Angola. And besides, do you see anyone else in this van getting anxious?”

I glanced around to see if anyone else was bothered by the danger. Conversations had continued without pause. Aside from the occasional idle glance out the window, no one was paying the drama any attention.

“No, I don’t,” I admitted.

Our van driver returned to the checkpoint guard. He said something that made the guard relax his grip on the rifle. He opened one hand and accepted the two packs of cigarettes our driver offered him. Pocketing them, he gestured to a structure adjacent to his building, and the two of them strolled toward it.

“You know, I’m not sure who won,” Carmen said.

I released the breath I’d been holding. “At least he didn’t shoot off his gun.”

Another uniformed guard crunched over to our van. “Descendez,descendez,”he called out in a bored voice.

Carmen and I exchanged worried glances. The volunteers in the van rose, grumbling and stretching.

“What’s going on?” Daniel, another English-teaching trainee, asked, frozen halfway between sitting and standing.

One of the volunteers shrugged. “Checkpoints….”

This wasn’t part of the plan and that concerned me.Wewere supposed to arrive at our training site in Lambaréné by mid-afternoon. We’d already stopped once for a flat tire and another time for a steamy, bug-infested half-hour, the reason never made clear. No one else seemed bothered by all these delays. Or worried. I could only fret to myself as we descended from the Peace Corps van into the staggering humidity, squinting at the overhead sunlight. Away from the city, deep inside the country’s interior, the whine of insects was a noisy symphony of clicks, buzzes and drones. Jungly trees crowded the landscape, broken only by the red-dirt road and clearing. A group of children, wearing an assortment of ragged thrift-store castoffs, shrieked at our sudden appearance and ran from us. The rifle-toting soldier and our driver had disappeared.

“But what’s the problem?” I quavered, trudging behind the others over to a mud-and-wattle shack set up next to the checkpoint station. “How long will we be here?”

“Who knows?” a volunteer named Rich replied. “Long enough to have a Regab.” He entered the shack and we followed like ducks. In the dim room, lit by sunlight filtering through cracks, Rich pointed to a table where our driver was sitting, relaxed in conversation with the guard. Both clutched wine-sized green bottles of beer. Regab.

“There’s malaria, of course,” Rich was telling us after we’d grouped around a back table, armed with our own tepid Regabs. “Then filaria, hepatitis, typhoid….” He ticked off the diseases on his fingers, undistracted by the whispers and giggles of the children who’d returned. Through gaps in the wall, I could see them outside: a half-dozen pairs of eyes watching our every move.

“Don’t forget giardia,” a woman sitting next to me on the bench sang out. “Purple burps and green farts,” she added for explanation.

“These are diseases a person might theoretically get here?” I asked.

“They’re diseases the volunteers have right now,”Rich replied.

“You’re telling me someone’s walking around with malaria?”

“That would be me,” he stated with obvious pride.

I scrutinized him. Tangled blond curls framed his gaunt, stubbled face, but there he sat across from me in a poncho-like shirt with wild swirls of color, swigging his Regab and chuckling as if having malaria were great fun.

“Aren’t you, like, supposed to be delirious and burning with fever?” Carmen asked.

He shrugged. “The fever and chills come and go. I feel like shit at the moment, but hey, might as well drink and have a reason to feel that way.”

I stared at him, uneasy. “I thought taking Aralen kept us from getting malaria.”

“In principle, yes. But it’s chloroquine-based and the mosquitoes are becoming chloroquine-resistant.” He wagged a finger at all the trainees. “You’re not safe from anythinghere.” At his pronouncement, the contents of my stomach—an earlier lunch of mystery meat in fiery sauce over rice—leapt around.

“Oh, don’t go scaring them,” the purple-burps woman told Rich, her pale, sweaty face earnest. “It’s been yearssince a volunteer in Gabon has died, and it’s usually from car accidents anyway. Aside from intestinal parasites and skin fungi, I’ve never gotten sick. If it weren’t for the stares that make you feel like a circus freak, and problem students in the classroom, life here would be a breeze. Well,” she added after a moment’s reflection, “except for those packages from home that keep getting torn into at the post office and arriving to me empty. Oh, and the loneliness, of course. That’s a killer. But hey, there’s Regab.” She raised her bottle and paused to regard it with something akin to reverence.

“Have you talked to Christophe about the post office business?” Rich asked her.

“No. Think I should?”

“Definitely. He might know someone there.”

“This guy, Christophe,” Carmen said. “I heard someone else mention his name. Is he Peace Corps staff?”

“Only as a trainer for you English teachers. But his father’s the Gabonese Minister of Tourism, so he knows a lot of people.”

Regab seemed exotic, heavier and darker than the Coors Light I drank back home, but very drinkable, in the end. It began to soothe my jangled nerves, numb my overstimulated brain. Sitting in a dark shack in the sultry equatorial African interior almost became the grand adventure it was supposed to be. Pinging foreign music blared from a battery-operated cassette player. Two chickens crooned and wove their way around our ankles, pecking at the dirt floor. Inconceivable to think that only five days prior, I’d been in Washington, D.C. with the other twenty-five Peace Corps Gabon trainees, beginning preparation for our two-year assignment.

The delay extended into another twenty-four-ounce beer. Apparently our driver didn’t have all the correct papers qualifying him to drive a group of us in the Peace Corps van. Chuck Martin, Peace Corps Gabon’s country director, also en route to the Lambaréné training, could solve the problem with a signature. When he showed up. I drank more Regab and pressed the bottle to my sweaty face. Carmen fanned herself with her Welcome to Gabon! leaflet. “I need to use a bathroom,” I mumbled to her. “Where do you suppose it is?”

“Got me.” She shrugged and grinned. “I think you need to go ask those friendly guys at the checkpoint next door.”

Instead I asked the bar owner, in careful textbook French, the next time she brought beers to our table. “Là-bas,” she told me, pursing her lips in the direction of the back door. Over there. “Follow the path,” she added in French.

“Want company?” Carmen asked.

“No thanks.” I teetered through the bar and stumbled outside where the brightness momentarily blinded me. The Regab, heat and jet lag had made me queasy and disoriented as well. But I found the path and started down it.

The forest directly behind the checkpoint station appeared scraggly, commonplace. The thin trees and spindly brush were like something I might have found in rural Nebraska. The number of flies, however, was remarkable, as was their tenacity. Waving them away from my ears, nose and mouth, I wandered down the foot-worn path, in search of the latrine. Past the clearing, weedy scrub rose on either side of the path, up to my waist. I began to wonder if my translation for là-basas “over there” was way off. Because I’d gone pretty là-basand I was nowhere. The marching cadence, however, relaxed me. In the past week, through the Peace Corps stateside training and the group’s transatlanticflight to Gabon, I’d rarely been alone. And I craved solitude the way I craved dance.

Dance. My ballet practice.

The thought made me stumble. To deflect my attention from the sadness that billowed up like a storm cloud, I focused on my sister, Alison. Alison and her boyfriend. The rage kicked in, clearing my head, making me feel strong again.

Okay, so maybe the Peace Corps business had been a mistake. At least it had offered me an escape. Nine months ago, back in September, Dad had given me an ultimatum. I’d just commenced my fifth year of undergraduate studies—the cost of changing degree programs twice—performing with a local dance company, enjoying life precisely as it was.

“Time to wrap it up, Fiona,” Dad told me. “Get that psychology degree—”

“—Sociology degree,” I corrected.

“Fine. Get your bachelor’s degree and go find work. A real job, not just dancing.”

Dutifully I dropped by the university placement center the next day, where I scanned the listings of job offers and recruiting interviews tacked up on the bulletin board. My heart sank further with each one I read. Actuary. Oscar Meyer sales rep. Claims adjuster. UPS supervisor. No, no and no. They all seemed to want to crush something unnamed and precious within my soul, that only dance brought me.

ThenI spied a Peace Corps brochure. Teaching English in Africa sounded responsible and yet romantic. To placate Dad and my own anxiety over leaving dance, I started up the application process. The CARE commercials on television, after all, had always touched me, with their drama and beautiful background music. I visualized myself, noble and selfless, helping rid the world of poverty. Africa would be reallife, a true adventure, yet something with soul.

The acceptance letter six months later, after a series of interviews, made me want to run the other way. Somehow my grand idea, viewed up close, had lost all its charm. I told my family about the letter, more for show than because I was going to do it. But while Mom and Dad congratulated me, I saw my two siblings exchange glances.

“You’re still playing with that idea?” Russell, the eldest and the family’s academic super-achiever, asked.

Alison, the family’s beauty queen—literally: she’d been Miss Nebraska four years earlier, in 1984—didn’tspeak at first. Her expression creased in bemusement before she shook her head and began to chuckle. “Oh, Fiona,” was all she said.

I knew what that shake of my older sister’s head meant. I’d seen it constantly through my bumpy, awkward, adolescent and university years. It was the pained look you gave someone who’d just stepped in dog shit. This, on top of the most recent humiliation and grief she’d caused me. I had to get away from her. The Peace Corps was my ticket out.

“Yes, I’m still ‘playing’ with that idea.” I glared at them. “In fact, I’ve decided to accept.”

And so I did it. Except now I was stuck in Africa for two years, thanks to my sister—and, admittedly, my pride. But I was going to stick it out, even if it killed me. Which, evidently, it might.

It dawned on me that I’d walked for a long time without seeing the latrine. “Screw this,” I muttered. Stepping away from the path, I squatted down to pee. Afterward, smoothing my skirt back into place, I turned around and headed back. But the return began to confuse me, after the path forked. I stopped and looked around. Had that grove of banana trees been there before? After another minute of walking, my heart began to pound against my ribs. I retraced my steps back to the fork and went the other way. It was worse—I recognized nothing. Fiveminutes later, I turned around again. This time, I could find no fork at all. Dizzy and nauseous, I began to trot, stumbling on a gnarled vine half-buried beneath the path. I followed the path until I came to a new fork. Or had I taken this fork? The overhead equatorial sun offered no directional clues. It sank in that I was hopelessly lost.

I dropped to my haunches, covering my face with my hands, my breath coming in short, panicked gasps.

“Eh… Ntang, wa ka ve?”

I dropped my hands and looked up. Like a mirage, a tiny, dusty African woman had appeared out of nowhere. She stood in front of me in bare feet, bent from the wicker basket load on her back. A twig poked out of her matted hair. She wore a sheet of fabric, the print faded with age, wrapped around her body like a bath towel. As I stood up, her face broke into a wide grin, revealing gaps from missing teeth. Her milky-brown eyes lit up in pleasure as she reached out with both hands to clasp mine in greeting.

“Ntang, wa ka ve?” she repeated, pumping my hand. She smelled smoky.

“Uh … bonjour.”I pasted a bright smile on my face.

“Ah, madame.” She beamed at me. In French, I explained I was lost, and could she help me find the checkpoint station? She bobbed her head and cackled. It dawned on me that she didn’t understand French. I imitated an AK-47 with my arms, putting a fierce look on my face. She nodded and patted me. She began talking, a patter of incomprehensible language in a soothing, hypnotic voice. Her face was serious, eyes riveted to mine as if this would make me understand her language better.

“I’m sorry,” I interrupted in English, my voice breaking. “I don’t understand a word you’re saying and I’m lost and I’m starting to freak out here. That stupid Regab…”

At this, her eyes lit up. “Regab, oye!”

“Regab, yes? Regab—to buy, to drink!” I mimed gulping down a big bottle, tossing my head back and making glugging actions. “Where—” I placed my hand over my eyes and with sweeping theatrical gestures, pretended to scope out the scenery, “—is Regab? With guns?”

This time she understood my rifle imitation. Taking me by the hand, she led me back the way I’d come. For a few minutes, I heard only the hushed rustle of the grass as we passed. Even the bugs seemed to be holding their breath.

We arrived at the fork. “Regab,” she said, and pointed to the right.

I paused. I’d tried this way already. She sensed my hesitation and made a little “eh” noise and nudged me down the trail. After a few steps, I turned around.

“Please, mama, this isn’t the right…” I started.

No one was in sight. The woman had disappeared into the grasses as silently as she’d come. A chill crept over me, in spite of the sweat pouring down my back. She’d been there and nowshe wasn’t. But I had no time to ponder the woman’s disappearance. Pushing down my panic, I hurried past the trees until I heard the sound of voices and laughter. The trail rounded a bend to revealthe clearing, the two buildings, the Peace Corps van, which, in my absence, had become two, with my fellow traineesand volunteers milling around.

Chuck, the Peace Corps countrydirector, a burly, vibrant man with a buzz-cut, had arrived. “Thereyou are, Fiona,” he said. “We were wondering what happened to you.”

“I don’t know where that latrine was that they were talking about. I went forever and got lost.”

He glanced to his right. My gaze followed his down a better traveled path, at the end of which stood a wooden outhouse.

“Oh,” I said. “Okay.”

As we walked together to where the others were starting to board the vans, I caught sight of the checkpoint guard. “Peace Corpse, oye!” he called out to everyone as they boarded. A broad grin nowcovered his face. He waved his arms, benevolent as a mother seeing her first-grader off to school, the image marred only by the presence of the rifle in one hand.

It was all too weird. I slowed down.

Chuck glanced over at me. “What’s wrong?”

It took me a moment to decipher my uneasy feeling. First, the rabid guard who was nowour buddy. Malaria Rich and his stories. Getting lost. The old woman. My intestines began to grumble, in tandem with my pounding head. I didn’t know what I’d seen out there or how I’d gotten un-lost or what had happened. Gabon was feeling a little like The Twilight Zone.

“It’s just that…things here don’t make sense.”

Chuck’s face widened into a smile.

“Welcome to Africa. You’ll be saying that a lot.”

Terez – Fiona is one brave young woman. I already feel like I know her! As far as chapter one goes, I’m hooked. Good on you!

Aww, thanks for the nice comments, Annette!

Myself, I see Fiona as being a bit of a wimp (and basically a chicken) in these first chapters, but she gets damned brave by the end. I really love her “bravery” trajectory through the story. Hope the reader will, too!