Ralph Vaughan Williams’s “The Lark Ascending” falls into that delicious category for me, of classical pieces I discover upon awakening. On weekdays I set my iPad alarm to an HD classical station and at 4:06am the music pierces my dreams, awakening me in the kindest of ways (until the “real” alarm blasts me out of bed at 4:30am).

It was over ten years ago when I first heard “The Lark Ascending,” courtesy of my wake-up alarm, and it was the most amazing thing. I lay there and listened, enraptured, to the lyrical violin solo voice, so very much like a bird, punctuated by a glorious, soothing orchestral backup voice. It was, I decided, the most perfect synthesis between nature and music I’d ever heard. It was the voice of something divine.

I sensed it wasn’t one of the composers I was familiar with. I’d have known. My thought of, “why don’t I have this composer’s music?” was followed by “just who is this magical composer?” When the announcer came on to give the composer’s name, it went in one ear and out the other. (Hey. In my defense, this was 4:15am.) I then promptly forgot about it until the next time it came up, a year later, in exactly the same situation. This time I got out of bed, and turned on the light in the bathroom to scribble his name down. Ralph Vaughan Williams. A mouthful of a name, in truth, with the curious pronunciation of Ralph (“Rafe”) throwing me off further. Months later I heard his “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” in the same manner, everything in me going very still so as to take in to the piece’s transcendent beauty. But even then I didn’t run to seek out recordings of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ music, nor read up about him. It was curious, to have connected so strongly with two of his pieces and yet know so little else about him. I now know he composed nine symphonies—had I heard any of them on classical radio? I don’t think so. Which means A) that I don’t listen to classical radio all that much, except when I wake up, or B) that his music is broadcast and performed more in England than in the U.S. Even though my husband and I lived in England for two years, I had no idea, in the end, just how venerable and important Ralph Vaughan Williams and his music are to the English.

I hope I don’t offend anyone if I say “But he doesn’t sound… English.” I think of the English as polite, conservative of speech and emotion, tasteful but subdued. The classical music I tend to like carries a certain edge. Or, better put, a distinctive cultural flavor. I’m coming to see that I enjoy subtly introduced folk elements from the composer’s native land. There are dozens of examples, but my favorites include: Dvorák and Smetana from the Czech Republic, Finland’s Sibelius, Norway’s Grieg, Hungary’s Ernst von Dohnányi and Belá Bartók, and toss in a few from Russia and former Soviet Union countries. And now, a new one for my list.

Ralph Vaughan Williams is grouped in the classification of “the Moderns” (or Modernists), the period following the Late Romantics that ended around 1915. (Think Prokofiev, Sibelius, Bartók, Bernstein, Ravel, Copland, Hindemith, Ives, Barber, Janáček, Stravinsky, Khachaturian, Rachmaninoff, Britten, Shostakovich, and the thorny, atonal Schoenberg.)

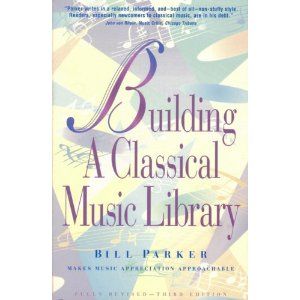

But let’s stop right there for a moment, because this fascinates me. Bill Parker, in his excellent Building a Classical Music Library, sums up my own feelings when he comments how it is difficult to find one thread that unites all the disparate styles of the Moderns. Do you ever wonder what makes 20th century music edgy, even when it’s not dissonant? Parker references that music era’s greater latitude for composers to use dissonance as an expressive tool, as well as a de-emphasis of melody, and greater freedom of form.

“Yet none of these quite enables us to add up to that thing we call the Modern style in classical music,” he writes. “The missing element in the equation is angst, that uniquely 20th-century pervasive feeling that somehow things are not quite right, that doom is possibly right around the corner. Angst is a 20th-century term born of two World Wars, economic depressions, the discovery of the id, the invention of the Bomb, and all the other dreadful things we all know about only too well.”

Well. That’s a very important, previously missing puzzle piece for me. It explains why I sometimes love, and sometimes dislike music — even as I respect it — from the Modern composers. And it helps explain the sound of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ work, as well. No, “The Lark Ascending” holds no angst. What it offers is a response to the angst in the world, an evocation of the English countryside, a hark back to a simpler, bucolic time that, with the rise of industrialization, seemed to be disappearing before Vaughan Williams’ very eyes. It’s soaring and yet nostalgic, fleeting.

I have lots more to say, but let’s give your eyes a rest and your ears a listen. I’ve always enjoyed Hilary Hahn’s performance of “The Lark Ascending,” so that’s where we’ll start.

Now let’s jump into what made RVW so distinctly himself. He was born in October 1872, in Down Ampney, Gloucestershire, into a family of means. From his mother’s side, he could claim two famous great-great-grandfathers, Josiah Wedgwood, the pottery magnate, and Erasmus Darwin, the physician, poet and grandfather of Charles Darwin. His father, a vicar, died when Ralph was not yet three, and his mother moved herself and her three children back to her own family home at Leith Hill Place in Surrey. There, Ralph grew up, receiving a well-rounded education that included music from an early age, before going on to boarding school. A month shy of eighteen, he entered the Royal College of Music, where he came to study with Sir Hubert Parry. He published his first music composition at age nineteen (although he’d written his own operas from age seven). He attended Trinity College, Cambridge, to study [or, in the lingo of the Brits, to “read”] history and music, earning [or “taking”] his B.Mus. in 1894 and his history degree a year later. He then returned to the Royal College of Music, where he became a close friend of fellow student Gustav Holst. In 1908 he would go to Paris for a three-month intensive to study modern coloristic harmony with Maurice Ravel, a formative experience. It was after this that he began to compose music in a highly original, distinctive voice, works like his String Quartet No. 1 in G minor and the transcendental “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” (which is so important and interesting and gorgeous, it merits its own blog).

The other important thing that fueled his compositions was his increasing interest in English folksong tradition. An avid collector of folk music, he scoured the countryside, accompanied by Gustav Holst, seeking out the ancient tunes before they could be lost amid the increasing industrialization of England. All told, he notated and recorded on paper more than 800 folk pieces.

He joined the British army at the outbreak of World War I, cutting three years off his age of 42 in order to qualify. His experiences there, in France and Greece, surely produced another facet of what made his compositions so rich. Michael Kennedy, the late English music critic, wrote that, on his return, Vaughan Williams “gave expression to the emotional experience of the war not in an angry outburst but in the reflective yet ominous quietude of A Pastoral Symphony [his Symphony No. 3], sketched in France in 1916 and in reality an orchestral requiem.”

Post-war, Vaughan Williams rejoined the Royal College of Music, this time as an instructor. As a composer, he continued to develop his own distinctive sound, with more advanced harmonies and, in later years, more edge and rugged abstraction. Because this was the Modern era, after all, and while he never ascribed to Schoenberg’s twelve-tone philosophy (thank goodness), he never slipped into a comfortable groove, utilizing the familiar, the derivative. Nine symphonies, concertos for piano, violin, oboe and tuba, five operas, chamber, ballet and film music, a large body of songs and song cycles, and other unaccompanied and orchestral choral works. These, and other works, earned him honorifics as the most important British composer of England since Elgar, living a fruitful, engaged life, right up to his death at age eighty-six.

But let’s jump back to “The Lark Ascending,” inspired by George Meredith’s 19th century poem by the same name. It runs 122 lines and, in all truth, doesn’t strike me as moving or inspirational enough to include here. But you can read it HERE. Vaughan Williams’ piece, “The Lark Ascending,” at the risk of stating the obvious, is an aural depiction a bird in flight. The solo violin voice is unspeakably beautiful. The end result is nothing short of amazing, and just fills the heart with joy. Vaughan Williams composed the piece in 1914 but did not yet publish or have it performed until 1920. There are two arrangements: one for orchestra and one as a duet for piano and violin. I haven’t heard the duet version and, in truth, I’m not sure I want to. Why mess with perfection? The orchestral version sounds like paradise.

Here is a different rendition of “The Lark Ascending,” performed by Nigel Kennedy. Tell me which version you prefer. This one, too, is sublime. It’s a bit longer and gorgeously stretched out.

I have to say I think I prefer Hilary’s version as well. Something of her delivery puts me in such a peaceful state. Both are wonderful but I “feel” more connected to Hilary’s performance.

Your insight to RVW is wonderful. I love learning about the composers and who they are almost as much as listening to their works of bliss.

Terez – as an Anglophile who listens to London’s Classic FM, I get to hear a good amount of Ralph Vaugh Williams. But this was a first for me. An exquisite first at that, including your spot on – even sublime – reflection on the piece and composer. Good on you!

I once had a similar experience while living there, waking up slowly to the simplest and purest piece of music I’ve ever heard. A piano piece by modern day classical composer Ludvigo Einaudi, “Melodia Africana”from his album I Gourni. I Iove it so much I set it as my morning alarm.

I’m so very glad we share this love of classical music that you bring to light!

Donna and Annette, I loved both your comments!

Annette, I have to tell you that, a few months back, I woke to something absolutely amazing and I knew it was more contemporary classical, almost like something in a film and, ta da! — it was Ludovico Einauldi. Maybe even the piece you’d suggested for your contribution to my “10 Happy Classical Tunes for a Pandemic” blog, “Divinere.” Thank you so much for alerting me to this wonderful composer.

Donna, I agree that Hilary’s interpretation is absolutely gorgeous. Her performances are very much the gold standard for this piece. The YouTube recording I linked is a bit problematic; the sound engineering isn’t ideal, and there are two giant, distracting noises from the audience during the performance. Ah, live music. But it’s so wonderful to watch her perform. She continues to be one of my faves among concert violinists. I had the privilege of seeing her perform the Korngold Violin Concerto in San Francisco, a dozen years back. It was sooooo good and memorable.

And I agree with you that half the fun of articles like this are delving into the composer’s life, finding what makes them interesting, what gives them humanity. By the time I published this, after whittling my musings down from 9000 words (sigh… I just can’t “write short”) to 1000+ words (in this case, VERY plus), I felt like I now really, REALLY knew and understood Ralph Vaughan Williams and his allure.

This is brand new to me and I love it!

I love your music posts! Pieces from Vaughn Williams usually stop me in my tracks; and Lark Ascending is my favorite; how nice to learn about his background. I’m not familiar with Max Bruch; its time to meet him. And It sounds like I need to hear “Melodia Africana” !

Thank you, Jess and MarySue, for chiming in! MarySue, Max Bruch is wonderful!! Lots of glorious violin concerto music. Love that pieces from RVW stop you in your tracks, too. Yup. It’s that kind of music.

The piece appears in Maria Peters’ movie ‘The Conductor’ about Antonia Brico which I happened to watch last night on Netflix.

Ooh, nice! Thanks for mentioning that, Martin. I’ll have to give the movie a peek on Netflix.