All right, a show of hands: who’s seen the 1832 ballet, La Sylphide? {{Looks around}} Yup. I’m not surprised. And for the record, I didn’t raise my hand either. But its importance came to mind last week, as I was researching for a Top 10 Classical Ballets list and found myself indecisive about the #10 slot. In the running were The Rite of Spring and Manon and La Fille Mal Gardée, among others, but ultimately I decided on La Sylphide, the oldest ballet in the classical repertoire. Turns out, however, that there’s so much to say about it, I couldn’t possibly squeeze all my thoughts into a lone paragraph, like the other nine on the list. La Sylphide needed its own blog. So, here we are.

And actually, the above was a trick question. The 1832 version, written and conceived by the tenor Adolphe Nourrit, set to the music of Jean Schneitzhoeffer, is not the one performed these days. For that, we must credit August Bournonville and his 1836 creation, same story but with different music (by Herman Severen Løvenskiold), different choreography, different intent (less dark and tragic). If you’re a ballet peep, you’re familiar with his name—the Bournonville style of ballet, created while he was ballet master of the Royal Danish Ballet, is known throughout the world today. And no other classical ballet gives us such a detailed glimpse of the early Romantic era and undiluted Bournonville technique. Watch this preview with excerpts from the Royal Swedish Ballet’s production and tell me if you find it distinctive.

Did you notice the low arms, the understated elegance of movement, the modulated arabesques and lack of flashiness? At the same time, there’s an emphasis on excellent technique and refined footwork. That’s Bournonville technique for you. That, and the fact that the ballet is almost 200 years old.

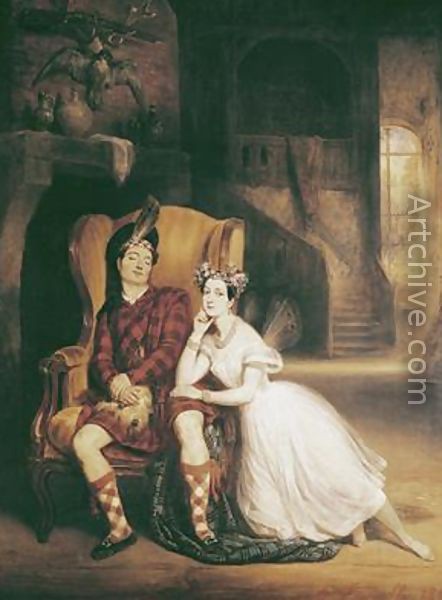

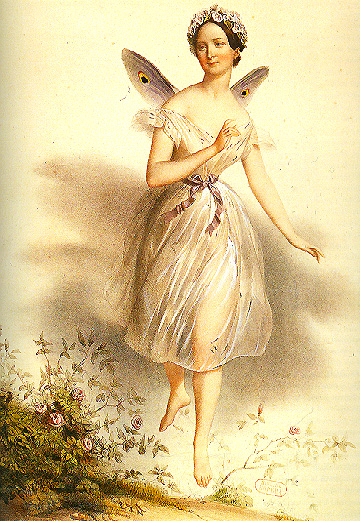

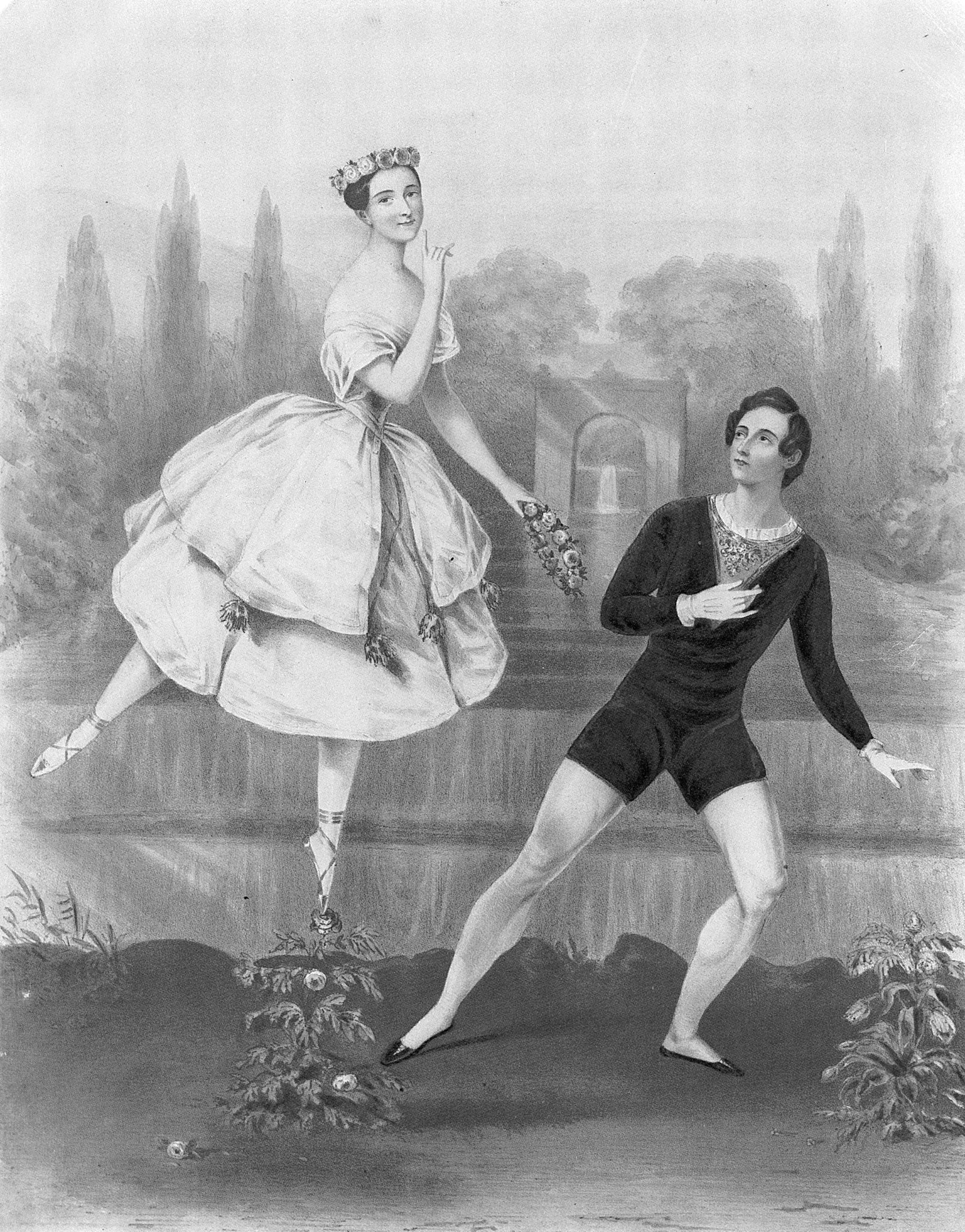

But we must credit the big premiere in Paris in 1832, with Marie Taglioni dancing as La Sylphide, and it was a momentous occasion for another reason too. Taglioni danced in pointe shoes, which hadn’t existed prior. Since they were nothing she could buy, she instead fortified her satin slippers with leather soles, darned the sides and toes to create a bit of a box at the toe base, and stuffed the tips with a little cushion and just made it happen, through incredibly strong legs and feet. (Want more history of her and pointe shoes? I blogged about it HERE.) Not to mention more than a little stoicism and iron determination. Because it had to have hurt like hell. But Taglioni was a professional and a perfectionist and the audience saw only the magical way she moved, expression utterly serene.

Let’s dig a little deeper together into why La Sylphide had such a strong impact on French society and the ballet world. It was post-revolution and there was profound disillusionment over all the change and its results. It’s hard for me to grasp the chaos and upheaval that the French Revolution wreaked on its inhabitants. It wasn’t just the 1789 event, heads chopped off, and back to business, albeit no longer run by a monarchy. There was Enlightenment rationalism, the 1830 Revolution, the Bourbon Restoration. Chaos, hope, disillusion, strife. Lather, rinse, repeat.

All this gave birth to a tremendous shift in thinking among the century’s artists and writers and philosophers. Let’s pause with the Sylphide business—but not really, as you’ll come to see—and take a look at one of France’s great men of literature, François-René de Chateaubriand (1768-1848). If you figure the “off with their heads” business took place circa 1789, and you look at his posh last name—his family had a château and lands in Brittany—you can imagine the kind of world, and threat to it, that he grew up in. The family was impoverished nobility, the latter of which probably saved their lives when the head-chopping commenced. Young François came of age amid this terrible violence and disruption, unheard-of cruelty and a reign of terror. As an adult, he served time in the émigré army before going into exile in London, exhausted and broken over it all. Like so many of his peers, he experienced a deep disillusionment that affected him and his craft to the core, prompting him to seek refuge in exploring a mystical, pre-Christian, medieval past, one leaving ample room for imagination, unbound spirituality, a misty realm that fed his soul. “Imagination is rich, abundant, full of marvels, existence poor, dry, disenchanted,” he wrote. “One inhabits, with a full heart, an empty world.”

Now, Chateaubriand’s philosophy embodied Romanticism, which I once naively took to mean everything was soft and pastel and romantic and happy endings and love and rainbows. Silly me. Instead, the writer/composer/painter who identified with the Romantic movement was prone, quite possibly, to fits of despairing suicidal reveries, melancholy ruminations, feverish broodings on love, the human condition, nature, and the roller coaster (my phrase, not theirs. Obviously) nature of euphoria and anxiety, forever coursing through the mind. It was a time of feeling the feelings, and making art from it.

You’re probably thinking, “Did The Classical Girl forget that this was supposed to be a blog about La Sylphide? She specifically told us this would connect to a Sylphide, but instead we’re getting a history lesson.” But here’s right where it gets interesting, and interconnected. Sylphides weren’t a 19th century invention; they existed in that fantastical plain of existence since the 16th century, and were well detailed in literature in the late 17th century. Fairies, angels, sylphs, spirits—they were all part of the same mystical club that verged on the world of the occult and magic.

Chateaubriand had his own sylph, who first came to him in the ‘delirious years’ of his adolescence, at the family’s medieval château, a perfect fairy-tale sounding environment, with lands, dark forests, stunning vistas of the surrounding country land, so it comes as no surprise to me that he would find solace in this imaginary creature, deeply feminine, an elusive yet eternal presence in his inner life. He described her as “composed of all the women” he admired, tweaking her image as he himself matured, adding the wise eyes of a village girl he knew, maybe mixing in the elegance of an older woman, and, from church, adding the grace and modest loveliness of the Virgin. Everything about the grand aristocratic world he’d loved and would lose, would find its way to her. And yet, a sylph is not a bland, sweet, obedient, comforting creature. Chateaubriand described her as a “magician” and an “elegant demon” who led him into frenzied states of uncontrolled imagination and desire. “An innocent Eve, a fallen Eve,” he wrote, “the source of my madness was an enchantress, a mix of mysteries and passions: I placed her upon an altar and I adored her.”

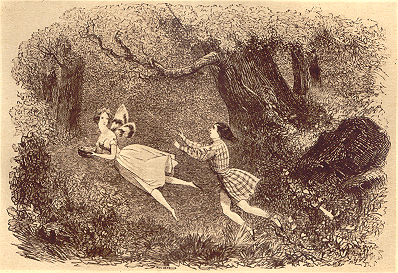

Okay, now picture this: in 1832, Chateaubriand is in Paris and decides to attend the opening of La Sylphide at the Paris Opera. There, before his eyes, he saw his sylph take human shape in the form of Marie Taglioni. Not only was it that she acted like “his” sylph, but he saw how James, the male protagonist, was just like him. No one else could see La Sylphide but James. She teased him, she wooed him; she most decidedly led him into those “frenzied states of uncontrolled imagination and desire.” James was set to marry the sweet, kind, village girl, Effie, but the Sylphide enticed him away, and there you had it. Chateaubriand had to have been quietly freaking out, to watch all this unfold onstage, the physical embodiment of his own sylph.

It quickly became clear that it wasn’t just Chateaubriand’s private ennui, this longing for something spiritual and ineffable during this troubling era in France. “Rationalism” meant the society was based on material wealth and had no place for spirituality and morality as its cornerstone. And for a huge number of people, that didn’t work. The French Romantics seized this counter-Enlightenment impulse and made it their own. La Sylphide struck a chord in the hearts of many, precisely during a time when it was most needed.

The public went crazy over La Sylphide. Critics adored Marie Taglioni in her lead role, describing her as a timeless religious symbol, a “celestial angel” of virginal purity who shone as a beacon in a “skeptical” age. And here’s the thing, too. Taglioni herself was such a virtuous figure offstage, that it raised the intrigue that much further. She was solidly bourgeois and respectable, which meant she could appeal to those embracing the non-Romantic aesthetic as well. Particularly fascinating to me, her dancing appealed deeply to women, who flocked to see her dance. You have to remember that ballet wasn’t very respectable as an art form or career, nor were female ballet dancers ever considered modest, model citizens. Taglioni and La Sylphide changed that.

It wasn’t just a sense of respectability that drew women to watch Taglioni and follow her adoringly, either. According to the Comtesse Dash, a literary figure of the time, women adored Taglioni because her dancing expressed a previously unconsidered truth about their own lives. To be a good, decent woman then meant you had to live carefully within the bounds of what society dictated—controlled, subdued, subservient. But beneath that, hidden, were powerful desires, strong emotions, pent-up passion. They could get a vicarious release watching the Sylphide, her lively spontaneity, her seductive touch, the way she moved as if floating above it all.

And now it’s time to fast-forward 183 years and the marvels of technology that allow us to sit back, relax, watch the screen and see The Most Important Ballet in the classical repertoire come to life before our eyes. Chateaubriand would have been green with envy at our riches.

PS: adding this late information that the above is NOT the Bournonville version but a 1972 Paris Opera Ballet version, choreographed and staged by Pierre Lacotte, inspired by Filippo Taglioni’s 1832 production. Lead roles danced by POB dancers Aurelie Dupont and Mathieu Ganio (Opera National de Paris, 2004).

So the full-length Sylphide that you linked just above — that’s the French version? It’s too bad that you didn’t say anything. The leads aren’t very good actors (compared to anyone from the Royal Danish Ballet).

Martin, I’m so pleased you brought this up! Yes, my bad, for not elaborating. Truth be told, I’m only discovering now that this is indeed the Paris Opera Ballet version, choreographed and staged in 1972 (and inspired by Filippo Taglioni’s 1832 production). Will now go into the blog itself and add this snippet! Leads are Aurelie Dupont and Mathieu Ganio

Opera National de Paris, 2004

I have loved spending the evening learning about ballet, which I have not thought of since taking lessons as a child. Great information, well-presented, fascinating, dreamy, and grand.. in turns.

Thank you, Heartland! I trimmed your reply, and, in turn, I trimmed from my article the line you felt didn’t belong. Good edit suggestion. We’ll just let this page be about La Sylphide and dance history. Glad you enjoyed learning more about ballet – La Sylphide history fascinates me, too.

Wonderful blog, erudite and beautifully written –thank you, Classical Girl.

One wish remains: that you had compared the two versions in detail. For example, in the original French version the Sylphide has a remarkably erotic trio with James and his bride-to-be. She interferes continually, seductively, in his wooing of the village girl, replacing his chaste attentions with her intoxicating insinuations. Dutiful marriage or romantic passion, is the tension of this choreographic moment. It’s an eroticism that is sourly absent from the Bournonville version.

I have seen this marvel only once, in a French TV documentary on La Sylphide, most likely danced y the Paris Opera Ballet in the 70s or 80s. I’ve been looking for it ever since. Do you have any information on this performance — or any others of this version?

Oh my goodness, Renate, I love your description of the original version. No, I have no information on that staging/performance, but I sure will be on the lookout for it now! Will reply here if I come up with something…

I saw Mikhail Baryshnikov dancing La Sylphide at Ontario Place August 14, 1974 with the National Ballet of Canada. The performance was unforgettable, punctuated with gasps from the audience at every leap and howls of applause for 20 minutes at the end. I was a recent starving student, and the fact that it was free as a thanks to Toronto and Canada for arranging Misha’s defection was just the topper. I have never been to a more stunning performance.

Margaret, how very cool! This was great fun to read — I could almost feel the audience’s thrill, the electric tension in the air. And that it was free — WOW, that is so great. I imagine everyone who was there will cite it as the most unforgettable performance they had/will ever see.