I was driving when I heard Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Violin Concerto the first time. It was a library CD I’d just borrowed, back in the days when most cars had a CD or cassette player and you could borrow handfuls of new music from the library. I was trundling down our hill in the Santa Cruz Mountains, with its trees and flowering bushes and redwood-studded hills, something that already fills my heart with pleasure. The final notes of the CD’s first concerto (Samuel Barber’s violin concerto) wafted through the air, followed by a pause, and then…

Magic. Cinematic bliss. It hit me like a thunderbolt, from literally the first note. That first melodic phrase catapulted me into a rich, tonally glorious world. It told a story; it promised adventure, intrigue, romance. It was an entire movie of emotions encapsulated into 25 minutes. Actually, nine minutes and three seconds, the length of the first movement. Really, it’s best not to be driving when you listen to it for the first time. I was so entranced I almost forgot where I was going. (Not a good thing on winding mountain roads.)

As you might guess, the Korngold Violin Concerto is on my Top 10 must-hear Violin Concertos list. But I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know until recently that Korngold’s claim to fame was that he was a film composer. Not that it was his only claim to fame, mind you. When he was born in May 1897 in Vienna, to a musical family—his father was a well-regarded music critic—it became clear, early, that he had a major talent. It was only a matter of time before he was drawing attention for his musical precocity. No one less than Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss declaring him to be a prodigy. When he was 11, his ballet Der Schneemann (The Snowman), became a sensation in Vienna, followed by his Second Piano Sonata which he wrote at age 13, played throughout Europe by virtuoso Artur Schnabel. There were two one-act operas premiered in Munich in 1916 and when he was 23, a full opera, Die Tote Stadt (The Dead City) premiered in Hamburg and Cologne. It was a lot.

Perhaps one of the reasons I knew so little about Korngold is that he is not mentioned in any of my composer and classical-music “bibles” here at my house. Was he not famous enough? Or possibly to the three respective authors, he was not “classical” but commercial. Was that a snub? Post-film-composing, Korngold’s classical compositions did find more than their share of skeptics and critics. One reviewer, upon the 1947 premiere of his violin concerto, described it, and the composer, as “less gold and more corn.” Korngold was “Hollywood,” after all. Tinsel.

But I have a strong, built-in “corn” detector, as a devoted listener. You don’t revisit a musical composition year after year, falling in love with it all over again, if it’s junk, or derivative, or sentimentalized. There’s something so much more going on here. It’s like Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No. 2, the way some purists consider its instant accessibility to mean lesser, even “lowbrow” entertainment [blogged about that HERE] and meanwhile, I am perennially astonished by its sweep, its intensity. The same can all be said for the Korngold Violin Concerto.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897 – 1957) was a phenomenal composer, and his gifts for fully fleshed-out musical ideas that created cinematic moods were extraordinary. He was a master of orchestration, of handling all the various voices in clever ways that came together like a master tapestry, all with the richly expressiveness that defined the longtime Viennese style of classical music and performing.

It was in the early 1930s that Korngold, then based in Vienna and garnering great acclaim, dipped his toe into film composition, at the request of Hollywood director Max Reinhardt. The approach of World War II and Hitler’s political ascent was a potent motivation; Korngold, as a Jew, could read the writing on the wall. He agreed to Reinhardt’s lucrative offer, and he and his family moved to Los Angeles.

Through the World War II, film composition was what Korngold did exclusively. It could be easily argued that the work saved his and his family, in myriad ways. It allowed him to work in a bubble of relative calm at something commercial that didn’t rip out his heart the way classical compositions might have, not to mention the painful awareness of the destruction of the genteel, artful, centuries-old traditions and way of life in Vienna, now in the thick of war.

While Korngold was working on the score of the 1937 Warner Brothers film, Another Dawn, he began to sketch a violin concerto based on the theme. The big question is, which came first? Chronologically speaking, the films did, and Korngold’s 1947 violin concerto clearly utilizes the same musical themes. As expressed in program notes for the Houston Symphony, “Whether the film score or the concerto sketches came first is difficult to know, but after an unsuccessful run through with a violinist who was not equal to its technical challenges, Korngold abandoned it. Perhaps he believed that he had written an unidiomatic solo part, but there may also have been deeper reasons for his laying aside.”

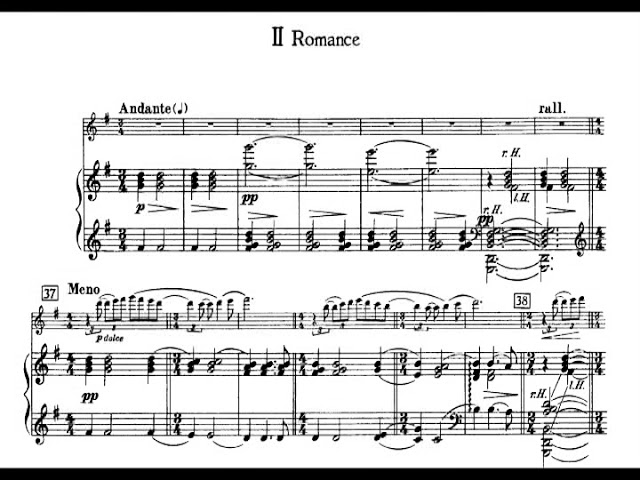

I adore the concerto’s first movement, the sweeping way it imparts a feeling of cinematic expansiveness. The second movement (“Romance”) has a silken touch and is sweetly lyrical, with just the right blend of imploring and romantic. It makes me think of a darkening summer evening. You know, the kind where the sun set earlier but still lends a glow to the western sky that softens into an increasingly deep blue overhead and, in the east, dots of stars are already punctuating the darkness. The violin carries the mood from soft and pensive to deep and rich, and all the colors in between. Yearning. Imploring. Contemplating. This is one of the reasons this is a hard concerto to play. The violinist must be able to coax this variety of colors and voices from the instrument. Oh, and do it really, really well. (Interesting factoid I only now learned: this movement takes its main theme from Korngold’s Oscar-winning score to the 1936 film, Anthony Adverse.)

The third movement is wildly different in mood, reminiscent of the way the Sibelius Violin Concerto sends you on a journey with three distinct emotional regions. Like that violin concerto, the Korngold’s third movement starts with a robust sound from the orchestra, before the violin leaps in with bold strokes, followed by pizzicato notes that accompany the melodic phrase it has passed on to the orchestra. There’s a rollicking quality with built-in momentum that propels the movement briskly forward. There are still pockets of melodic expansiveness, and a gorgeous stardust moment where Korngold has inserted one last slow, lovely passage. Then the concerto speeds back up. And now, hold on tight, listener, because both orchestra and solo violin race like two side-by side trains that have no intention of stopping until they arrive amid fanfare (and braking) at an explosive conclusion.

Before I share the whole shebang with you, let’s have some fun. Here’s a trailer of the film, the 1937 Warner Brothers’ classic, Another Dawn, re-posing that “which came first?” question.

Now let’s give the whole concerto a listen with violinist Hilary Hahn, who does this so beautifully. Featuring the Deutsche Symphonie Orchester with Kent Nagano conducting.

I should mention that for many, many listeners, the gold standard is the 1954 recording performed by Jascha Heifetz, who performed at the concerto’s February 1947 premiere in St. Louis. (An interesting factoid: Heifetz loved it but encouraged Korngold to increase the technical difficulties of the solo part, which he did.) Me, I don’t know. I acknowledge Heifetz is a master, one of the best violinists of all time. But for this concerto? I guess I love Gil Shaham’s rendition, the one I heard first. Coming late to the party tends to make you form different attachments. The cheese dip was all gone, so I fell in love with the hummus that hadn’t even been put out until an hour into the party. I would, therefore, take the hummus over the cheese dip in the future because, hey, I was hungry, it was perfect, and why change anything?

You be the judge. Should this be the gold standard? Here’s the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QCbAsGQwz40

And of course I must share the recorded version I first heard, that day, years back, when I was driving down our hill and was struck by musical lightning. Featuring Gil Shaham and the London Symphony Orchestra, André Previn conducting.

Which one is your favorite?

The Hilary Hahn was my favorite. I love this violin concerto so much!

How did I not know about this incredible piece of music???

Loved hearing from you, Jess and PJ!

And PJ, I know, right?! I felt the same way, the first time I heard it.