“Tout un monde lointain, absent, Presque defunct, vit dans tes profondeurs, forêt aromatique,” (A whole distant world, absent, barely alive, dwells in your depths, oh scented forest.)

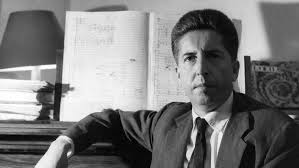

Mstislav Rostropovich commissioned this cello concerto. The poetry of Charles Baudelaire inspired it, albeit loosely. Pierre Boulez disdained its composer, Henri Dutilleux, and his work, which might be why Henri Dutilleux isn’t as famous as Pierre Boulez, who played such a big part in the contemporary classical music scene in post WW II France.

The concerto’s full title is “Tout un monde lointain… (‘A Whole Distant World…’) for Cello and Orchestra.” I heard it for the first time in 2011, performed by the San Francisco Symphony, featuring cellist Gautier Capuçon. It begins with an ever-so-soft, shimmery sound, a stiff metal brush against a drum head that commences the first movement. Dutilleux claimed that at the night of the concerto’s premiere in Aix-en-Provence, right as the concert began, in that instant, “a new breeze began gently to rustle the leaves of the plane tree, like the sound of waves and very similar to what I had been searching for when I wrote the score.” Which is a pretty cool thing to have happen. And thus, under that magic spell, the cello begins, offering its contemplative reply.

Listening, I felt as if I’d been transported inside a movie. One of those older ones, the kind you saw first as a kid, and it utterly engrossed you, encapsulated you, and of course it had a great soundtrack; it was all about the soundtrack, and was likely a mystery, a black and white one, a thoughtful movie, something sort of Twilight Zone-ish.

French-born and trained Gautier Capuçon, as the soloist, was sublime. This was the second time I’d seen him perform and his efforts never fail to render me starry-eyed with admiration and infatuation. He had a thoughtful, intelligent way of playing the concerto, head angled in, as if he were finding the notes, the music, that was there, deep within the cello. He wasn’t making music so much as releasing it into the air. I can’t decide if his stellar playing is in part due to his charismatic good looks and demeanor or that the two simply go hand in hand with him. I first saw him perform the Schumann Cello Concerto in 2009 and, like this night, was completely wowed by him and his performance. My verdict: he is both sublimely talented and pleasing to watch perform.

Dutilleux, a mid-to-late 20th century composer who died in 2013, was not a serialist, a twelve-tone-ist, a modernist, a sentimentalist. He shunned “isms” and set styles, and composed from his own well of individualism and carefully crafted creativity. His career was one of “quality not quantity” and won him many accolades and commissions from world-class musicians and ensembles, although he was certainly not a household name, even within the classical music world. Plenty of classical music aficionados have never heard of him or his music. Which is a shame, because this guy composed some damned incredible music. Which is why I’m glad I have The Classical Girl to give Henri Dutilleux a post-humous shout-out.

His music is striking. Moody, evocative, conjuring up colors and complex feelings and moods that you’re not sure how to define. And yet, lest we all get too sentimental, in alternating movements of “Tout un monde lointain…” the cello gets feisty, the music harsher, more dissonant. The brass lets out a blast and there’s all sorts of drama going on. Like cockroaches crawling around in the night and you turn on the light in a room and they all scatter in a panic.

But just when the third movement of “Tout un Monde Lointain” had me thinking I didn’t really like the concerto that much, the fourth movement brought the strumming of a harp and a return of the dreaminess, albeit with an edge to it—an uneasiness, a mystery, but the kind that draws you in, captivates you. Like seeing a blood-red rose poking out of a snow-covered yard on an overcast winter twilight, and you don’t have shoes on, so you don’t go to check it out closer, you just marvel at the sight. It’s cold and you’re alone, but there’s that compelling, mysterious sight.

The concerto’s final movement brings the listener back to agitation, lively discord, melodic but not, with the cello’s final notes just sort of trailing off, as ambiguous an ending as they come. I left the concert hall an hour later, slightly discomfited, not sure exactly what I remembered, or would remember. Perhaps just the memory of Gautier Capuçon’s artistry, those slower, pensive moments where he was bent over his cello, finding those notes, releasing them into the air for the spellbound audience to catch.

This article first appeared, in different form, at Violinist.com. You can read it HERE.

I’m a cellist, and I’ve never heard of this work! Thank you for sharing. I’ll be chasing this down now.

Ooh, cool, Amanda! Here’s a link I have of Lynn Harrell performing the concerto: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9eh-cMkdS0