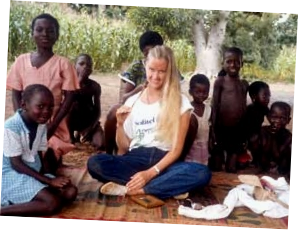

Today The Classical Girl has once again put on her fiction writing cap. Now, if you read this August blog post of mine (https://www.theclassicalgirl.com/classical-girls-black-ivory-soul/), you’ll know what this is about. If you haven’t read that post, well, please go do that. Because that’s chapter one of A Dancer’s Guide to Africa, formerly titled Black Ivory Soul, my novel about a ballet dancer who’s set off to Africa for two years, joining the Peace Corps, largely to escape her sister’s bitter betrayal back home. Of course, over there in Gabon, she lands into bigger problems.

Here’s chapter two; I’d love it if you gave it a read. Fiona, ever the fish out of water, is learning how to teach English. Or not. And make friends. Or not.

Clicking on the link just below will display the text in a clean, pretty pdf style. Or read on, below, for the WordPress-formatted version (= ugly).

Ch 2, A Dancer’s Guide to Africa

A DANCER’S GUIDE TO AFRICA

Chapter Two – Training

Twelve Gabonese students regarded me as I approached the front of the classroom. Through the latticed walls that doubled as windows, I could see across the dusty courtyard into another classroom, where a fellow English-teaching trainee was performing the same show. I turned to face my students, adolescents in blue and white uniforms. They sat at their desks, eager and expectant, their hands folded on the wooden desktops. Aside from the shrieks of nearby roosters and the rattle of trucks over potholed roads, silence reigned. The girls’ dark eyes, fixed on me, seemed both innocent and worldly. The boys looked younger, painfully shy. Whenever they stood to speak, their hands swooped down to cup their genitals.

It was the first day of practice school, after three weeks of preparing with trainers. My voice shook with nervousness. Sweat dampened my cotton blouse. The students, all here voluntarily, repeated the five new English vocabulary words after me. By the end of the hour, they were turning to each other and asking, “What’s this?”

“It’s a pen.”

“A pencil?”

“No, it’s a pen.”

“Oh. Thank you for the pen!”

And like that, they were chatting in English, these kids who’d never spoken a word of the language before setting foot in this classroom. They could greet me, confirm whether a pen or pencil was in my hand, thank me and say goodbye. It felt like a small miracle.

Beaming, I looked to the back of the room to see if Christophe, my trainer, could appreciate how well I’d done. He stood there, arms folded, his expression cool, assessing.

I’d blown it when I first met him, but in my defense, I’d had other things on my mind. Like survival. Acclimating to this strange new place I lived. Absorbing impressions that had flashed by too fast since our arrival: the complexity of French; the rickety dorm beds; the communal bathroom with its stand-up toilets and the sour, bitter smell of a zoo on a hot afternoon; the names of my African and American trainers.The morning of our first teacher training session, I’d still felt rattled and disoriented. But I’d tried to be helpful, moving surplus boxes out of our classroom for Meg, the training coordinator and education volunteer leader. Unable to see around an oversized stack, I bumped into someone when I approached the door. The boxes tumbled to the floor as both of us recoiled with murmurs of annoyance. When we straightened, we met at the same height of five-foot-eight. I hadn’t seen this guy before. I would have remembered. The other African trainers were vibrant, well-dressed and confident, but still friendly and accessible. This stranger seemed as polished and unapproachable as a movie star in his starched button-down shirt and tailored trousers. His skin was the color of melted Hershey’s chocolate. Startling green eyes punctuated his regal, fine-boned face.

“You’re tall.” He spoke the words with disdain, easily pronouncing the “r” that plagued the other African French speakers on the compound.

I was accustomed to exceptionally attractive people, having shared a home with one for many years. I’d learned not to feed their egos. Furthermore, this guy had knocked down my boxes but frowned at me as though it had been all my fault.

“No,” I matched his tone, “it’s just that you’re short.”

Silence followed. Shocked outrage swept over his smooth face, as if I’d pulled up my shirt and flashed my breasts at him. Before either of us could apologize or introduce ourselves, however, Meg breezed in and surveyed the scattered boxes. “Whoops,” she said, “Christophe, how about giving Fiona a hand here?”

“I’d be happy to help Fiona.” He glanced at me again, his expression now unreadable.

So this was theChristophe, the government minister’s son. I’d just insulted one of the most important Gabonese in the Peace Corps community. I wanted to cry. Instead, I grabbed half the boxes, deposited them where they belonged, and made a beeline to the courtyard, framed by a cluster of low, whitewashed buildings, where I hovered out of view until our session started.

But Christophe was all composure and decorum in the classroom thereafter. He was, I had to admit, a highly qualified trainer. He’d taught English in Gabon for four years and spoke perfect, idiomatic English from his years of living in Washington, D.C., where his father had been a high-ranking diplomat. I disliked the stylehe advocated, though: overly structured and unsmiling. I thought teaching English should be more like a show. I’d spent years performing onstage; I knew you had to smile and act lively in order to engage your audience. His method made no sense. When I complained in a training session, he asked me who the trainer was. I whispered to Carmen that he must have forgotten who the native English speakers were. This elicited a snort of laughter from her, but glares from Christophe and Keisha, another one of the trainers.

After the first practice class, Christophe met with me to discuss my teaching. He wore cologne, an expensive-smelling citrus blend that made me want to lean in closer to sniff his neck, a prospect so idiotic and alarming, I felt even more uncomfortable around him.

“You see your ‘entertainment method’ working here,” he said, tapping his pencil on the critique form for emphasis, “but you had twelve students, all of whom wanted to be here. At your post, you will have anywhere between thirty and eighty students in a room the same size. Once the novelty of having a pretty American teacher wears off, they will grow bored, undisciplined.”

The determined set of his face left no room for further discussion. But that wasn’t going to stop me. I raised my hand timidly.

He frowned. “There’s no need to raise your hand. What is it?”

“If they grow bored, aren’t you, as the teacher, responsible for presenting something more interesting?”

His face remained composed, but he took a long time to breathe in and out before replying. “The teacher’s job is to teach. That is the role for which I am training you. Please endeavor to focus on that.”

I offered him a bright smile. “Thanks for the feedback! I’ll be sure and keep it in mind.”

He didn’t smile back. “I hope you do.”

**

French class and cultural awareness sessions followed practice school. Afterwards, I escaped to the dorm room Carmen and I shared, a cramped space that held a desk, plastic chairs and two rickety metal-framed cots. I dropped onto my mattress, a pad with the thickness of sandwich bread. Carmen found me there ten minutes later, reading.

“You spend too much time in here,” she said. “Robert and I are going into town for a beer. You should join us.” She and Robert, another English-teaching trainee, had become close friends, hitting it off when he admired her combat boots. Carmen ran her hand through her hair to freshen her spikes before nudging my cot. “C’mon, I won’t take no for an answer.”

Lambaréné was one of Gabon’s main cities, a large inland island that bisected the Ogooué River. The smell of waterlogged foliage battled with the diesel fumes of rumbling trucks and overripe odors from the market, a noisy place choked with people, dust, chickens and produce. Robert led us through the crowds to his favorite bar, the backyard of a bright blue house on the periphery of the action. We found seats under the protection of a giant coconut palm, at a picnic table.Inside the house, pots clanged in dinner preparation. Outside, hens clucked, children giggled and shouted. A goat snuffled through nearby weeds. This was my favorite time of the day in Gabon. As the afternoon light grew soft, the golden rays mingled with wood smoke that curled up from neighborhood cooking fires. The air smelled sweet and comforting.

“Perfect,” Robert announced. He struck me as a person who knew these kinds of things. During our training in Washington, D.C, he’d smoked Gitanes and drunk Pernod, items as exotic to me as caviar and hashish. He was a native New Yorker and always wore black tee shirts, particularly ones advertising obscure rock bands. Today it was Cantankerous Wallababies. Yesterday, it had been The Zodiac Debriefers. The only rule was it had to be black. “It’s a New York thing,” he told me, pushing his floppy brown hair from his face.

A woman sailed past, basket on her head, baby on her back and toddler clutching her hand. She turned without losing balance of her load and shooed away a group of loitering kids. They scattered, only to regroup around the bar, staring at us. One boy, older than the rest, took a few steps closer. He wore torn gym shorts and a grayish tee shirt displaying a fading, improbableLos Angeles Yankeeslogo. “Bonsoir,”he said.

“Bonsoir,”the three of us replied.

The boy stayed. “If you please,”he began in halting English. “The hair on madame.Is this the true hair?” He pointed to my hair, which I’d freed from its ponytail. Robert and Carmen swiveled around to scrutinize it too.

I hated my hair. There was too much, it was unruly, and the color defied categorizing. Strangers would approach me back in Nebraska and demand, “Just what color isyour hair?” The answer was usually expressed in the negative: not brown, not blond, not auburn, but an odd combination of everything. “Like sunlight filtering through autumn leaves,” Mom would tell me.

“Like dirty pennies,” Alison would scoff. Another thing it wasn’t: a duplicate of her honey-blond tresses, groomed religiously to create a sleek curtain against her face. My sister got the enviable color, I got the scraps. Like our eyes. Hers were the intense blue of a cloudless winter sky, while mine were the palest blue possible, as if Alison had used up the pigment when she was born, eleven months before me.

“Yes,” I told the boy, “this is my true hair.”

He took a step closer, followed by the other children, who reached out to touch it. African hair, a stateside trainer had informed me, didn’t grow much at all. My long hair would draw attention. The kids oohed and aahed before skittering away. The boy with the Los Angeles Yankeesshirt flashed us a thumbs-up before joining the others.

“I’m already hungry,” Carmen announced. “I hate those fish head and rice lunches.”

“Better to have the fish heads served at lunch than dinner,” Robert said. “That means they’ll have something better tonight.”

Fish heads still freaked me out. The first time I’d seen a serving pan of them, three dozen heads all staring with glassy eyes, I’d thought it was a practical joke, and that the real main course would be out once everyone had had a good laugh at Fiona’s reaction. But the Gabonese server had only regarded me expectantly, repeating his question of whether I wanted one head or two.

“The thing that annoys me,” Carmen said, “is how you have to pick and dig at that spot between their eyes—do fish have foreheads?—to get any decent meat.”

“Yes, but they say the eyeballs are a delicacy,” Robert said. “I tried one today.”

I stared at him. “What was it like?”

“Crunchy. Piquant.” He seemed pleased by my reaction.

“I remember the time my parents tried to force caviar on me,” Carmen said. “It seemed very important to them that a child of theirs enjoy it. What snobs. I told them not a chance, I’d rather starve. It became a battle of wills. My father said no other food until I tried at least a bite of it. I said fine. And so I went thirty-six hours without food.”

“Who won?”

“I did.” Carmen grinned. “My mom couldn’t handle the stress of it.”

“You were a devil child,” Robert said, chuckling.

“I was. My dad liked to tell me that their original plan had been to have multiple kids, but after I came along, they didn’t think they could manage more.”

“I would’ve loved to have been an only child,” I said wistfully.

“Don’t be so sure. It can get lonely.”

“Better to be lonely than to always be arguing with them.”

“Do you miss them?” she asked.

I paused to fortify my response with a gulp of Regab. “I’m not sure.”

“Fiona… That’s an unusual name for a Midwesterner,” Robert said.

“My mom loves musical theater. She was going through her Brigadoonphase.”

“I heard you say you used to perform.”

“Yes. Ballet.”

“Did you know the training compound has an auditorium with a stage?”

“You’re kidding!”

Robert grinned at my open-mouthed reaction. “Nope. It’s behind the other buildings, near the grove of palm trees. Nothing dramatic, just a big room with a stage.”

“Can anyone use it?”

“I don’t see why not. It’s not locked or anything. The only time I’ve seen it in use is on Wednesday afternoons for the staff meeting.”

“So you think I could slip in there and use it on Saturday afternoons?”

“Give it a try.”

**

On Saturday afternoon, I changed into a leotard and sweatpants, and grabbedmy ballet slippers and cassette player. I’d brought none of my pointe shoes to Africa. They had short life spans under the best of circumstances, and within a dozen sessions in this hot, humid environment, they would have been as soft as my infinitely more comfortable leather slippers.I hurried through the courtyard, dried leaves scudding in my wake,until I found the auditorium. The door was indeed unlocked. I trembled with excitement. Once inside, I opened a few of the shutters that doubled as windows, letting light pour in. I surveyed the room, the size of an elementary school assembly hall. The stage, a narrow wooden platform rising three feet high, was hopeless. The floor, however, once cleared of chairs, made a perfect dance space.

Using the backs of three folding chairs as my barre, I placed my leg on one and stretched over, hand around my calf, face against my shin. As the tightness in my hamstrings eased, a sense of unexpected happiness welled up in me.My chattering thoughts slowed. To the lilting strains of Chopin, I began barre with pliés, tendus and dégagés, just like back home, in every ballet class I’d ever taken. Right side first, swiveling around to repeat the exercise on the left. I could almost hear the teacher’s soothing voice, leading me onward, through ronds de jamb, frappés, développés.Muscles I hadn’t used in six weeks reawakened. The burn in my quads, my calves, felt good. I even welcomed the cramping in my feet as I arched and pointed, pausing afterward to massage the knot, flex and re-arch the toes, holding the position in a relevé balance.

Once I’d completed barre, I switched out cassettes. I’d made a compilation tape of favorite ballets and pieces I’d performed over the past few years. I would start, I decided, with Interludes, a ballet set to symphonic music by Saint-Saëns, with a mix of both energetic and lushly romantic variations.

Themoment I heard the opening notes, the hard shell inside me dissolved, and I slipped right back into performing mode. Two counts of eight, near stillness, except for a pulse of the arms. Another, bigger pulse. Thenmovement, a sauté-chassé run, sweeping the perimeter of the performing space, heading to its center for a lunge with a full port de bras for my arms. Deprived of my practice for so many weeks, the energy poured out of me. The moves flowed, one into the other, polished and precise. My développé and arabesque extensions were absurdly high for someone who hadn’t danced for six weeks. Pirouettes were rock-solid, doubles and triples, with clean landings, another unexpected gift from the dance gods.

I’m home again. I’m safe.

For the next several minutes I danced, utterly absorbed, spirits rising ever higher. The brisk first movement ended and the second movement, the adagio, began. The music here was heart-stoppingly beautiful, the melody supported by the low, sonorous chords of an organ played so softly, you could feel more than hear it. The choreography was equally sublime: a romantic pas de trois, myself the lone female interacting with two males, who supported me in promenades, turns and lifts, even as I remained elusive. I could almost feel my partners’ presence, the brooding drama, the longing and desire the adagio and its music stirred up. Dancing it alone didn’t feel wrong. Instead, the mood it created became even more dreamy and haunting. Almost like a sacred experience, one touched with mysticism, as I moved alone-but-not, practically fibrillating with the power a good performance always produced.

The movement ended with another deep lunge that gradually brought me down to sitting, legs at right angles. To the adagio’s final notes, I shut my eyes, arched back and slowly lifted my arms to the sky.

Pure magic. My throat tightened. Prickles passed over my arms, my back, like a shimmering wave of heat. Power, indeed. But as the music wafted away, so did the safety. The mystical feeling hovered in the air for a moment longer, just out of reach, before disappearing.

The third movement commenced, brisk and propulsive, relentlessly forward.

My hands dropped down to my side. Gone, that other world. Replaced by sweaty, magic-less, inescapable reality. I shifted, pulled my legs close, rested my forehead on my knees and began to cry, choked sobs that shook my body.

The music played on. I didn’t move. But when a creak by the door drew my attention, it dawned on me I had a visitor in the back of the room. Someone well dressed, regal in his posture, in his authority. A hint of expensive-smelling citrus cologne dispelled any doubts as to his identity.

I couldn’t believe my bad luck. Then anger replaced disbelief. This was myspace. Here, Christophe was the foreigner, the intruder. And even though the magic had disappeared, the power still hovered in the air. It was my power, and he knew it.

I rose and strode over to the cassette player, which had moved on to the cheery finale. I snapped off the music and in the newfound silence, I turned and regarded him, unsmiling.

He, too, was unsmiling. He looked almost stricken.

“I’m sorry.” He gestured to the door. “But it was unlocked…”

“Yes,” I conceded.

He began to walk toward me. “How long have you danced?” he asked. His voice held a note of respect that, I would have argued, was impossible for someone like him to produce.

“Since I was seven.”

“Why did you stop?”

“To come here.”

“Were you a professional dancer?”

I shook my head. “Just a college student, performing in a local company.”

“You’re very good.”

It felt odd to hear him compliment me. “Thank you,” I said, searching for my towel to mop my sweaty face. “How long were you watching?”

“When I heard the Saint-Saëns from the courtyard, I came over here.”

At this, I regarded him with surprise. “How did you know that was Saint-Saëns?”

He frowned. “Do you mean, oh, how could an African possibly be familiar with classical music?” He relaxed, waved away my stuttered defense. “An educated guess, in truth. I’m thinking his Symphony No. 3? The Organ Symphony?”

Impressive. I nodded.

“It’s quite distinctive,” he said.

“It is.”

“My mother taught me to enjoy classical music,” he said. “She’s half French. She grew up in Paris and had a lot of exposure to it. During the years we lived there, we attended the symphony, but it’s the Paris Opera Ballet, of course, that’s the big draw there.”

He was right; the Paris Opera Ballet was as big as it got, right up next to the Kirov, the Bolshoi, The Royal Ballet.

“It’s nothing I expected to see in the Peace Corps,” Christophe said.

“No. Me neither. They don’tblend too well, do they?”

“Maybe not. But I see you didn’t let that stop you.” He smiled, which transformed his face, his whole persona, into something dazzling. A mock-stern expression followed. “This certainly explains that habit you have of performing in the classroom.”

This time, I could only laugh. As I tried to wipe the sweat off my face with my arm, he pulled a neatly folded, monogrammed handkerchief from his pocket and tossed it to me. I caught it with a grin. I knew at that moment—the way you know about a good pair of pointe shoes—that a friendship had just begun.

**

Okay, I just had the time tonight to read both chapters of your novel . . . and I’m dying to read more! Please keep posting excerpts

Oh, Kitteacat, you just made my day. Seriously. : )

PS: guess what – we just brought home a new kitty cat. A little 3 month old kitten. Yesterday morning he was exploring what was in my near-empty coffee cup (it was tea) and even stuck his head in for a few laps. All I could think of was Kit-Tea-cat. Like you! LOL!

Wonderful! A new addition to the family just in time for the holidays! Dont forget to sneak him a bite of turkey =)