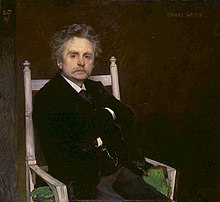

I love visualizing the 25-year-old Edvard Grieg in 1868, married just one year and already the father of a newborn daughter, right as his composing career was taking off. I can’t decide if it was artistic zeal or the exhaustion of jugging so many roles that made him seek retreat that summer at a secluded spot in Denmark, where in a flurry of inspiration he wrote his Piano Concerto in A minor. I’d say he hit the ball out of the park.

I recently wrote about Grieg HERE, a Norwegian composer whose music so delights me, I gave him two blogs. It bewildered me, then, to discover the whole world didn’t find Grieg as iconic, genius and ingenious a composer as I do. Consider the following:

- “It is true that nobody can make a case for Grieg as one of the immortals.” (Harold C. Schonberg in The Lives of the Great Composers)

- “As a child my first favorite composer was Edvard Grieg, who would not make anyone’s list of all-time greats.” (Anthony Tommasini, The Indispensable Composers – a Personal Guide).

- “Grieg was only twenty-five when he wrote his piano concerto,” writes Bill Parker, in Building a Classical Music Library, “and it shows. Its structure is partly cribbed from Schumann’s concerto (in the same key), the various sections are awkwardly joined together, repeats and restatements are repeated verbatim without even minimal alterations to increase interest.”

Fortunately, Parker goes on to say this: “But nobody cares about such academic concerns (except, of course, academics); what people hear are the fresh melodies and the enchantment of their poetry. It has become the very prototype of the Romantic Piano Concerto and Sergei Rachmaninoff, for one, considered it the greatest ever written.”

Let’s give it a listen. You’ll be greeted with a glorious opener that simply can’t be ignored. Yes, it sounds like the Schumann Piano Concerto’s opener, and resembles the concerto structurally. But otherwise, for me, Grieg’s concerto is singular. The performer, one of my concert-pianist favorites, is Leif Ove Andsnes, performing with the Bergen Philharmonic, conducted by Ole Kristian Ruud.

What did you think? Did those sweeping melody lines carry you away? What about the inventive nature of each new one, the little folkloric touches? I love all three movements equally, and yet there is something particularly lovely about the second movement. I return to this concerto annually; it seems to be a late summer thing, and every time I first hear the familiar, beloved Adagio commence its gorgeous melody, tears sting my eyes. The more stressed out I am, the more it affects me. There is something so timeless and comforting about the music. They say change is the only constant, and I gotta be honest, “change” exhausts me much of the time. But this recording of this music, written over 150 years ago by a gifted 25-year-old who embodied music that arose from a divine place, seems to rewrite that rule. Yes, it’s a recording and thus frozen in time. But the music taps into a deep spring that flows eternal, and my feelings, in the twenty years I’ve listened to this, haven’t changed. Which makes me so deeply grateful that art like this exists, to remind me of all that is timeless, noble and beautiful about this world we share.

Another one of my favorite moments in the concerto is a passage late in the third movement. It’s like a second adagio movement within a movement, where the mood becomes soft, dreamy, like dusk. The piano’s musical line and orchestra become a call-and-response, and perfectly evokes the mood of the natural world. Like the soft breezes that come late in the day, stirring the air oh, so gently. There’s this moment where the pianist and the composition both seem to reach perfection. Everything slows and grows quiet, and what ensues are these mere pulses of the softest music. It sounds like nature breathing. It’s stunning. I can’t think of any other concerto that gives the listener such a broad, imaginative palette of tonal flavors and textures.

Since I don’t play the piano myself, I love hearing concert pianists’ thoughts about their experience in practicing and performing big works like this. In Gramophone UK’s “Master Class” article on Grieg’s Piano Concerto, virtuoso Stephen Kovacevich says this:

There’s steel behind the Concerto’s virtuoso element. I would hope that people aren’t seduced by the wonderful lyricism into neglecting the brilliance and dissonant qualities of the piece. Omnipresent are vitality and a bittersweetness. It’s very much dance music, but you should avoid making it too square, rhythmically. At the same time, Grieg’s melodic contours have the quality of yearning or wistful melancholy – they’re seldom straightforwardly joyous. There’s always an ambiguity which performers must bring out, but it’s not a conscious thing; you just go for what you finally think the essence of the passage is.

It’s a great article and includes similar insightful contributions from pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet. Check it out HERE.

One interesting factoid I discovered is that Grieg himself was dissatisfied with the concerto and would go on to regularly revise it, through the rest of his life. The version we hear today is quite different from the version that early audiences in Denmark and Norway heard (it premiered on April 3, 1869, in Copenhagen and in Christiania–now Oslo–on August 7, 1869). There were seven revisions that included a total of 300 changes, although the melodies themselves remained the same throughout.

Hungarian composer and piano virtuoso Franz Liszt became a friend to Edvard, in ways that were to significantly impact the younger composer’s career. Liszt’s reputation in this era can’t be understated; he was essentially the central figure of the Romantic movement. A prodigiously talented pianist with a rich, colorful personal life (note to self: give him his own blog), he worked tirelessly to promote and assist his fellow pianists’ and composers’ efforts (Grieg was both). Before ever meeting, Liszt viewed a copy of Grieg’s piano sonata, was impressed, and penned a letter to Grieg, complimenting him on the composition. Grieg was beyond thrilled; having a glowing reference from such an esteemed source meant Grieg could more confidently request from the Norwegian government a grant that enabled him to study in Rome. There, he was able to meet Liszt, and spend two memorable afternoons in his company.

The encounters proved to be extraordinarily fruitful, as Grieg chronicled in a letter. We of the 21st century are very fortunate here, as Grieg was a prolific and very readable letter writer. The following is excerpted from Grieg and his Music, by Henry T. Finck (2nd Edition, New York, 1909), a noted American music critic and author at the time, to whom Grieg sent a treasure trove of his personal letters. This letter, chronicling Grieg’s second visit to Liszt, was written to his parents on April 9, 1870. (He’d brought a copy of his piano concerto, having just received it back from a publisher in Leipzig who had refused it. It would take Grieg three years to find a publisher for the concerto.)

[My friend] Winding and I were very anxious to see if [Liszt] would really play my concerto at sight. I, for my part, considered it impossible; not so Liszt. “Will you play?” he asked, and I made haste to reply: “No, I cannot.” Liszt took the manuscript, went to the piano, and said to the assembled guests, with his characteristic smile, “Very well, then, I will show you that I also cannot.” With that he began. I admit that he took the first part of the concerto too fast, and the beginning consequently sounded helter-skelter; but later on, when I had a chance to indicate the tempo, he played as only he can play. […]

Toward the end of the finale […] he suddenly stopped, rose up to his full height, left the piano, and with big theatric strides and arms uplifted walked across the large cloister hall, at the same time literally roaring the theme. When he got to the G in question he stretched out his arms imperiously and exclaimed: “G, G, not G sharp! Splendid! That is the real Swedish Banko!” He went back to the piano, repeated the whole strophe, and finished. In conclusion, he handed me the manuscript, and said, in a peculiarly cordial tone: “Fahren Sie fort, ich sage Ihnen, Sie haben das Zeug dazu, und — lassen Sie sich nicht abschrecken!” (“Keep steadily on; I tell you, you have the capability, and — do not let them intimidate you!”) This final admonition was of tremendous importance to me; there was something in it that seemed to give it an air of sanctification. At times, when disappointment and bitterness are in store for me, I shall recall his words, and the remembrance of that hour will have a wonderful power to uphold me.

Allow me to end with another composition of Grieg’s that I adore, his Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, op 45. In that Griegian way of his, this sonata is like no other in the violin repertoire, with its fresh, intriguing melody lines and folkloric touches. If you’re a Grieg fan and haven’t heard this before, you’re in for a treat. An added perk: this recording features not just acclaimed violinist Christian Tetzlaff but my fave pianist, Leif Ove Andsnes.

PS: Want to read about two other concertos that drew criticism from the academics–silly academics!– but are absolutely stunning? Check out my blogs on “Is Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 Lowbrow?” and “Khachaturian’s Sizzling Piano Concerto”

Thank you for this very interesting view of Grieg’s piano concerto!

Greetings from Norway.

Frodo.

Ooh, I LOVE being greeted by a resident of Grieg’s native Norway. Thanks so much for the comment and the greeting, Frodo! I’m humbly grateful that you enjoyed the essay.