When I listen to Debussy’s “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun,” often referred to as simply “Afternoon of a Faun,” I’m reminded of the vertiginous feeling of gazing at a 3-D computer-generated picture, one that, once you’ve allowed your eyes and brain to shift slightly, draws you inside a world you previously hadn’t been able to see. Here, now, you’ve entered a phantasmagorical place, with spiraling, descending pathways and billowing shapes that your eyes can slide down or climb up, respectively. A world where the tried-and-true rules don’t apply. I don’t know about you, but I love the feeling, the sensations. It never fails to take me on an inner journey, far from my mundane thoughts, the dreary to-do treadmill of daily life.

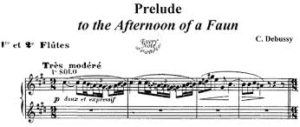

It’s no surprise Debussy’s “Afternoon of a Faun”—or “Prélude à L’Aprés-midi d’un Faune” in its original French—is one of my favorite short pieces of classical music. It’s held me in its grips from the moment I first heard its opening solo flute notes, the responding call by a horn, a harp. Debussy was not a “follow the set rules” kind of guy. He was pretty much the opposite. In his compositions, the “rules according to my tastes” deliver volumes of sensation. A warm afternoon. A time long ago, back in the days of mythical creatures. Nymphs and fauns and lush foliage and shimmering waves of summer heat. Unexpected emotions rise, within the music and the listener both. Languor, sensuality, euphoria, curiosity, an awareness of the exotic. You are flung back to your own childhood, your adolescence, all awash in new experiences, colors, sensations. You are every place you’ve always wanted to be, your heart contracting and expanding, seemingly at the same time. For ten fleeting minutes, you let the music cradle you, transport you. Afterward, it leaves you disoriented and a little dizzy. You stumble away, back to the everyday world, your everyday life, and yet forever altered from the experience.

I like to imagine how the audience must have reacted in that opening performance in Paris, 1894. This was still the Romantic era, after all, with its conventions on tonality, scales, sequences. Audiences were used to hearing Beethoven and Brahms and maybe a little Wagner if they were feeling the urge for something turbulent. Chopin, earlier, had dazzled with his pianistic originality, just as Saint Saens had managed to impart a touch of the exotic into his own compositions. But Debussy? He was young, still rather green, known to chafe against the constraints the masters before him, through the years, had mandated in musical composition. He loved literature and art, and for Prélude à L’Aprés-midi d’un Faune, he’d taken, as inspiration, a poem by one of France’s greatest poets at the time, Stéphane Mallarmé, and his 1876 creation, “L’Aprés-midi d’un Faune.” The poem was a work of art, having taken the poet a decade of deep searching, pondering, revising, to come up with a finished, published product that was, in his mind, music already. (Mallarmé was part of the “symbolist” movement of poetry, that, in a nutshell, strove to evoke, to illuminate, elaborate on the human condition,) So, here’s this 1894 concert hall audience, all expectant, knowing the poem: sensuous, story-like musings of a faun—mythical half man, half goat—and his erotic pursuit of two nymphs on a warm, drowsy afternoon. The lights in the concert hall darken, the musicians ready themselves, the conductor raises his baton, and you hear… this.

Stirred you, didn’t it?

If you’re like me, you might wonder what sort of mystical alchemy was involved, that Debussy’s music can do so much more than, say, Brahms, whose music is decidedly masterful and at the top of its craft. I think It has to do with the fact that, like the symbolist poets, there was a drive to consider the vast sprawling world of inner feelings, the human condition, the resolutely ineffable. It’s interesting to note that the French poets of this time, which Debussy so admired, considered music to be the pinnacle of art — not necessarily the music you hear in a concert hall, so much as the “music” that arises from the finest of art works. Mallarmé’s reaction to Debussy’s turning his poem into “real” music is debated–some say he was pleased, and complimented Debussy on the effort. Others say he mildly resented that his poem, so full of “music” already, was now eclipsed by Debussy’s music. The guy had a point. Who hears the title “Afternoon of a Faun” and thinks, “Ah, yes, that poem! Mallarmé’s opus!”

Care for 10 interesting factoids about Debussy? Here you go!

- He was born Achille (pronounced as a “shhh”)-Claude de Bussy in 1862.

- In spite of an aristocratic-sounding name, he came from a poor family and was schooled at home (while his siblings were shipped out), obtaining private piano lessons more by unexpected circumstances and good fortune more than planning and good funding.

- He was accepted to the Paris Conservatory of Music at the age of 10, where, over the next eleven years, they would endlessly chide him for “courting the unusual” and encourage him to deliver something “more befitting of his great talent,” which was to say, the same old thing they’d been hearing for generations.

- He was the 1884 recipient of the highly prestigious Prix de Rome, which gave him a four-year residence at Rome’s Villa Medici, which he hated, and was miserable, and [barely] lasted two years before returning to his beloved Paris, where he lived for most of his life.

- While he resisted much of the traditional schooling that came his way, both in music and academia, as an adult, he read voraciously and enjoyed socializing with the literati. He was a frequenter of Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous Mardis (Tuesdays) salon, the place for poets, artists and literary minds to gather in 1890’s Paris.

- His musical inspiration came frequently from poetry. I’ve shared, in past blogs HERE and HERE the way this shows up in the works, “Clair de Lune” and “Beau Soir.”

- Debussy had originally planned for this work to be three part: a prelude, an interlude, and a paraphrase finale. Sidetracked by work on his opera after he’d completed the Prelude, he dropped the idea of two more parts.

- Wagnerian opera, and Javanese gamelan music, fascinated and engaged the young composer, each playing a part in his artistic development, leaving an imprint that would resurface in his music.

- Even though Debussy’s work was considered by many to be the peak representation of musical impressionism, he himself disliked that term, and saw himself as a “modernist.”

- He died during the final year of World War I, unable to have a public gravesite funeral service because of the constant aerial bombing of the French capital by the Germans.

Above all, Debussy was a composer who defined a moment—that in which the classical music world would begin to question all rules of harmony and composition. “Works of art make rules; rules do not make works of art,” he once famously said. While he’s still considered by most to be a Late Romantic composer more than of the Modern school, you can see him and his style’s clear demarcation. Tchaikovsky and Brahms, Dvorák, Grieg, Liszt, all came before. Bartók, Prokofiev, Ravel, Sibelius, Shostakovich and Stravinsky all came after. Pierre Boulez famously pronounced Debussy’s “Prelude to an Afternoon of a Faun” to be “the beginning of modern music.”

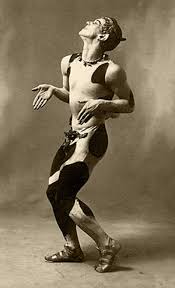

I find it so fitting that Debussy’s ground-breaking “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun” should be utilized, eighteen years later, by another legendary, ground-breaking artist. In 1912, ballet phenomenon Vaslav Nijinsky, then with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, created his ballet, “Afternoon of a Faun.” He was the lead dancer; no one else could have done it justice. No one else could have so shocked the public, foretelling a new, modern realm of dance to come. The vitality, originality and willful disdain of long-held rules that Nijinsky brought to his art makes him seem like Debussy’s twin. And for Nijinsky, much like Debussy, the newness and overt sensuality of the opening performance in Paris shocked and disturbed some of spectators. This was not the art they’d come to know and had grown familiar with. This was new and vivid, with all sorts of new flavors and textures to consider. It didn’t just stir the soul, it stirred… other parts.

But we’ll leave this blog to Debussy. Not only does Nijinsky deserve his own blog, the National Ballet of Canada will be coming to San Francisco in April to perform “Nijinsky,” John Neumeier’s evening-length ballet about the man, his art, his madness. The Classical Girl is SO looking forward to this production. I’ll be posting a blog preview of the production in the week to come. (Editor’s note: it’s done and you can read it HERE.) In the meantime, however, I can’t resist giving you a flavor of what happens when Debussy and Nijinsky–and we mustn’t forget Stéphane Mallarmé’s poetry–put their considerable talents together for an unforgettable “Afternoon of a Faun.” The dancer is Rudolf Nureyev, another legend that some day I’ll devote a blog to. This recording is old, which, in my mind, only adds to its sensuous, evocative allure. I can feel Nijinsky’s presence all the more clearly.

All right, I have to add one more. It’s taken from the 1980 Herbert Ross film, Nijinsky. So it’s Hollywood’s version of Nijinsky premiering “Afternoon of a Faun” in Paris’ Theatre du Chatelet. It’s really good, and allows you to see certain nuances up close. But, be warned. The end of the ballet is… racy. But so was Nijinsky. Pushing those borders. And so was Debussy. All for art. Give it a look, if you dare. (Warning, this music will stay in your head ALL DAY once you’ve left this page. My apologies.)

Okay, one last thing, and this time I mean it..

Mallarmé’s 1876 masterpiece poem is damned long. But it’s lush and sensuous, and, really, you sort of do need to read the poem in order to understand what both Debussy and Nijinsky were striving to put into music, and movement, respectively. This is one of several translations that exist from the original French. If you read and find it lacking, please do share a translation you feel is better.

L’Aprés-midi d’un Faune

These nymphs, I would perpetuate them.

So bright

Their crimson flesh that hovers there, light

In the air drowsy with dense slumbers.

Did I love a dream?

My doubt, mass of ancient night, ends extreme

In many a subtle branch, that remaining the true

Woods themselves, proves, alas, that I too

Offered myself, alone, as triumph, the false ideal of roses.

Let’s see….

or if those women you note

Reflect your fabulous senses’ desire!

Faun, illusion escapes from the blue eye,

Cold, like a fount of tears, of the most chaste:

But the other, she, all sighs, contrasts you say

Like a breeze of day warm on your fleece?

No! Through the swoon, heavy and motionless

Stifling with heat the cool morning’s struggles

No water, but that which my flute pours, murmurs

To the grove sprinkled with melodies: and the sole breeze

Out of the twin pipes, quick to breathe

Before it scatters the sound in an arid rain,

Is unstirred by any wrinkle of the horizon,

The visible breath, artificial and serene,

Of inspiration returning to heights unseen

O Sicilian shores of a marshy calm

My vanity plunders vying with the sun,

Silent beneath scintillating flowers, RELATE

‘That I was cutting hollow reeds here tamed

By talent: when, on the green gold of distant

Verdure offering its vine to the fountains,

An animal whiteness undulates to rest:

And as a slow prelude in which the pipes exist

This flight of swans, no, of Naiads cower

Or plunge…’

Inert, all things burn in the tawny hour

Not seeing by what art there fled away together

Too much of hymen desired by one who seeks there

The natural A: then I’ll wake to the primal fever

Erect, alone, beneath the ancient flood, light’s power,

Lily! And the one among you all for artlessness.

Other than this sweet nothing shown by their lip, the kiss

That softly gives assurance of treachery,

My breast, virgin of proof, reveals the mystery

Of the bite from some illustrious tooth planted;

Let that go! Such the arcane chose for confidant,

The great twin reed we play under the azure ceiling,

That turning towards itself the cheek’s quivering,

Dreams, in a long solo, so we might amuse

The beauties round about by false notes that confuse

Between itself and our credulous singing;

And create as far as love can, modulating,

The vanishing, from the common dream of pure flank

Or back followed by my shuttered glances,

Of a sonorous, empty and monotonous line.

Try then, instrument of flights, O malign

Syrinx by the lake where you await me, to flower again!

I, proud of my murmur, intend to speak at length

Of goddesses: and with idolatrous paintings

Remove again from shadow their waists’ bindings:

So that when I’ve sucked the grapes’ brightness

To banish a regret done away with by my pretence,

Laughing, I raise the emptied stem to the summer’s sky

And breathing into those luminous skins, then I,

Desiring drunkenness, gaze through them till evening.

O nymphs, let’s rise again with many memories.

‘My eye, piercing the reeds, speared each immortal

Neck that drowns its burning in the water

With a cry of rage towards the forest sky;

And the splendid bath of hair slipped by

In brightness and shuddering, O jewels!

I rush there: when, at my feet, entwine (bruised

By the languor tasted in their being-two’s evil)

Girls sleeping in each other’s arms’ sole peril:

I seize them without untangling them and run

To this bank of roses wasting in the sun

All perfume, hated by the frivolous shade

Where our frolic should be like a vanished day.

I adore you, wrath of virgins, O shy

Delight of the nude sacred burden that glides

Away to flee my fiery lip, drinking

The secret terrors of the flesh like quivering

Lightning: from the feet of the heartless one

To the heart of the timid, in a moment abandoned

By innocence wet with wild tears or less sad vapours.

‘Happy at conquering these treacherous fears

My crime’s to have parted the dishevelled tangle

Of kisses that the gods kept so well mingled:

For I’d scarcely begun to hide an ardent laugh

In one girl’s happy depths (holding back

With only a finger, so that her feathery candor

Might be tinted by the passion of her burning sister,

The little one, naïve and not even blushing)

Than from my arms, undone by vague dying,

This prey, forever ungrateful, frees itself and is gone,

Not pitying the sob with which I was still drunk.’

No matter! Others will lead me towards happiness

By the horns on my brow knotted with many a tress:

You know, my passion, how ripe and purple already

Every pomegranate bursts, murmuring with the bees:

And our blood, enamoured of what will seize it,

Flows for all the eternal swarm of desire yet.

At the hour when this wood with gold and ashes heaves

A feast’s excited among the extinguished leaves:

Etna! It’s on your slopes, visited by Venus

Setting in your lava her heels so artless,

When a sad slumber thunders where the flame burns low.

I hold the queen!

O certain punishment…

No, but the soul

Void of words, and this heavy body,

Succumb to noon’s proud silence slowly:

With no more ado, forgetting blasphemy, I

Must sleep, lying on the thirsty sand, and as I

Love, open my mouth to wine’s true constellation!

Farewell to you, both: I go to see the shadow you have become.