So you’re acquainted with Antonin Dvořák’s buoyant, instantly accessible “New World Symphony,” are you? And you loved it? Yay, you are part of an enormous fan club that has a spectacularly broad base of listeners. So, what other compositions of Dvořák’s do you like?

{{Silence}}

Ah.

I get it. I was there too, once.

But here’s what happened. In my younger years, I binged on Dvořák’s enormously popular Symphony No. 9, subtitled “From the New World” or, as the average person knows it, the “New World Symphony.” Through high school and college, I couldn’t get enough of it, first my dad’s LP record on the stereo, and in college, a cassette recording on my tinny cassette player. After graduation, when it was time to leave for the Peace Corps, I bought a portable cassette player, for my dozen classical-music cassettes. Yes, the New World Symphony made the cut. Yes, I overplayed it. You do the math: boredom + homesickness + craving for cultural thing x two years. I loved that music as much as chocolate. It brought my former elegant, cultured world of the arts right into my spartan living room, if only for an hour at a time. The music never failed to transport me, comfort me in my homesickness. I played those beloved cassettes till the tape itself snapped (did you know you can fix this problem with scotch tape? Necessity is the mother of invention).

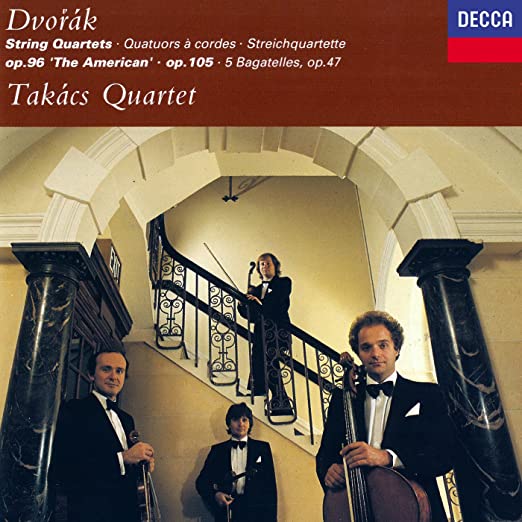

So, okay, I overplayed Dvořák’s New World Symphony and alas, I have never felt the hunger for it in my later classical music-listening days. Even if it’s on my subscription series at the San Francisco Symphony, I’ll trade it out for something different. Now, in spite of this, I’ve still considered myself a huge fan of Dvořák’s. In the ‘90s, I acquired CDs of his Slavonic Dances and then his Serenade for Strings, and very much enjoyed them both. But it wasn’t until 2005, when I was researching for my novel-in-progress, looking for an appealing string quartet to assign to my violinist character, that I struck gold, a CD that featured his Quartet No. 12, known as “The American.”

“The American” is buoyant, fresh and imbued with such delicious colors. It’s so unlike any other classical quartet I’ve heard. The first movement takes us on a lively, vivid journey, the four instruments passing melodies from one to the other before coming together as a dynamic, lyrical force. In the gorgeous, soulful slow movement, the voices of the first and second violin seem to weave around and tumble over the other, tangling, embracing and releasing with a sigh. The third movement sounds like birdsong (literally and intentional—the scarlet tanager). And finally the fourth movement ties up everything so jauntily, at its rousing conclusion, you want to leap to your feet and cheer.

More fun about this CD discovery: the first five tracks feature the composer’s “5 Bagatelles.” One of the instruments is, curiously, a harmonium. Prior to this, I’d only heard a harmonium being played in a yoga class. This gives Dvořák’s “5 Bagatelles” a decidedly unique sound. Finally, the CD includes Dvořák’s Quartet No. 10. Whoa! Only here did I learn he’d composed a total of 14 string quartets. And they’re all great. What riches! How did I not know this, prior to 2005?

So let’s talk about the composer and his distinctive sound. With a detour, first, to elaborate on his illustrious predecessor, fellow countryman and composer, Bedrick Smetana (1824-84) and his opera, The Bartered Bride. Trust me, I’m not leading you astray. And all you need to know for now is that Smetana was the first Bohemian/Czech composer to embrace and incorporate Bohemian folk song as the basis of his classical compositions.

Here’s how Harold C. Schonberg in The Lives of the Great Composers puts it:

“In The Bartered Bride, a flawless work of comic art, Smetana fell back upon the reservoir of Bohemian polkas and other dance music, though he did not quote directly. He invented all of the melodies. The opera is so spiced with the very spirit of the country that many find this hard to believe, but Smetana was proud of his ability to avoid direct quotation, and there is none of it in The Bartered Bride. Ralph Vaughan Williams, the British composer, tried to analyze Smetana’s method of work and came to the conclusion that ‘Smetana’s debt to his own national music was of the best kind, unconscious. He did not, indeed, ‘borrow,’ he carried on an age-long tradition, not of set purpose, but because he could no more avoid speaking his own musical language than he could help breathing his native air.’ […] The exoticisms of the Bohemian musical language were not in the Western classical musical consciousness until Smetana appeared. His language is, on the whole, a happy language. When Bohemian composers express melancholy, it is in a delicately elegiac way, without the crushing world-weariness and pessimism of the Russians. More often, Bohemian music expresses joy, happiness, dancing, festivals.”

AHA!!! Thank you, Mr. Schonberg, for putting a finger right on what I like about Dvořák’s music and why it holds enormous appeal to so many listeners. And, indeed, although Smetana was the one who founded Czech music, it was Dvořák, twenty years later, who popularized it.

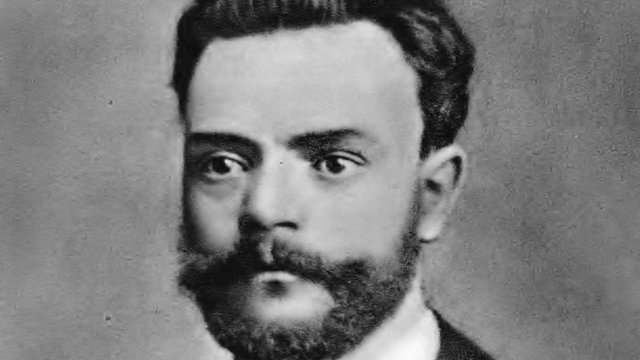

A few facts about Antonin Dvořák. He was born on September 8, 1841, in a Bohemian village called Nelahozeves, thirty miles from Prague. He was the eldest of fourteen children, although only nine of them survived past infancy. His was a humble, hardworking, music-loving family. His mother was a former serving maid in a lord’s castle and his father was an innkeeper, sausage-maker and amateur zither player. Young Antonin showed an early talent on the violin and also sang in the church choir, all the while training in the family shop to become a butcher like his father.

It soon became clear, however, that Antonin’s future lay in music-making, not sausage-making. By twelve, he was taking more advanced lessons on the violin, and when he was sixteen, the family sent him to the Institute for Church Music in Prague. He studied harmony, piano and organ, already at work in composition as well. After graduating in 1859, he composed, took on students and played the viola professionally with the Bohemian Provisional Theatre Orchestra. For well over a decade, he would work tirelessly, endlessly, not yet garnering any attention or praise for his compositions.

In 1873, Antonin married Anna Čermáková and they immediately began a family. She gave birth to nine children total, although tragically, their first three children all died of various diseases within a few months of each other. Fortunately, the six that followed would go on to thrive. Antonin left his position with the Provisional Theatre Orchestra and took a position as an organist in St. Adalbert’s church in Prague, which provided greater financial stability, higher social status and ample free hours to devote more time into composing.

A turning point in Dvořák’s fortunes came finally in 1877, when he entered a competition, the Austrian State Stipend for Composers. He won, and drew the attention of Johannes Brahms, one of the competition’s judges; the two would become lifelong friends. Brahms, highly impressed by Dvořák’s entry, recommended him to his publisher, Fritz Simrock, one of the most popular European publishers of that time. He, too, was impressed with Dvořák’s work, and published first his Moravian Duets and soon thereafter, his Slavonic Dances. They were a huge hit.

Through the 1890s, Dvořák’s career and fame steadily increased. He visited Russia and conducted orchestras in Moscow and St. Petersburg. In 1891, he was given an honorary degree by the University of Cambridge. He was offered the position of Professor of Instrumentation and composition at the Prague conservatory. Then in 1892, he was offered an incredibly lucrative directorship in New York (25 times what he was being paid in Prague) with the newly established National Conservatory of Music. He and his family remained there for three years and I’ll give you three guesses, reader, what he wrote in this time.

Yes. His New World Symphony. His Quartet No. 12, “The American.” The latter, it turns out, he composed in a mere two weeks, during the idyllic summer of 1893 in the town of Spillville, Iowa. The town had become a Bohemian enclave, earlier immigrants creating a slice of their homeland, for which Dvorak was decidedly homesick. He and the family returned to Prague themselves after his New York directorship, but the fruits of his “American” labors would stay with us forever.

I think this is a good time for a Top 10 List.

Classical Girl’s Top 10 Dvorak Faves

- Klid (“Silent Woods”)

- Romance in F minor

- Quartet #12, “The American”

- Slavonic Dances #2 in E minor and #4 in F major (op. 46 and not op.73)

- Violin Concerto in A minor

- “In Nature’s Realm”

- Cello Concerto in B minor

- Symphony No. 8

- String quartets 10 – 14

- Serenade for Strings

Honorable mentions abound: his “5 Bagatelles,” the “Carnival” Overture, his “Symphonic Poems and Overtures.” Oh, and his “Songs My Mother Taught Me.” I’m curious to know which Dvořák composition is YOUR favorite?

Finally, it’s only fair that I include a performance of his enormously popular, tried-and-true, “New World Symphony.” Enjoy. And then go share it with your non-classical music friends.

Love me some Dvorak! 🙂

And Smetena has a special place in my heart since our trip to Prague.

Yes, I thought of you, MarySue, as I was penning this blog, knowing how you love Dvorak. And remembering, as well, the time we hummed the catchy “Ma Vlast” tune together that is so infectiously delightful. The one that went “Dum dum de da de da da DA da da, da dum de da de da da, DA de da da.” I can hear you humming it now over the cyber waves — you’ve got it!

I just came across the link to this article this morning at The Imaginative Conservative. Unfortunately, I have been unaware of your writings until now and I am so excited to spend time catching up on what I have missed the past seven years. When thinking of my favorite composers, Dvorak is usually the first name that comes to mind, although I truly love many others, especially Brahms, Schubert, Mozart, Vivaldi, Vaughn Williams, and of course the great Beethoven (so many others as well). I cherish Dvorak’s later string quartets and other chamber music such as the piano quintets and quartet. So much energy and beauty! It is a happy day that I have found you. Thank you.

Stephen, your response here has made my day. My week. My month. This is why I continue with my labor-of-love-with-no-monetary-gain writing about classical music. For readers like you. (And because, well, I can’t not write about this thing I love so passionately.) So THANK YOU SO MUCH for the gift of your reply. And welcome! Always a delight to “meet” another classical music lover. I wrote two blogs, last year, about Ralph Vaughan Williams, so if you haven’t hunted them down yet, check ’em out!

Thanks so much—so glad to have stumbled upon this, albeit a year late! Dvorak is indeed a wonderful composer, among my favorites—as an oboist (and occasional English Horn player) I particularly enjoy playing Dvorak 9, although my favorite piece of his is actually Quartet No. 13.

Quick correction, though: Scarlet Tanager is not the bird cited in his American Quartet. That is a clear misidentification. For all his musical talents, Dvorak was not a birder. It sounds much, much more like Red-eyed Vireo to my ear, and as I recall some folks (Ted Floyd?) wrote a detailed analysis that came to the same conclusion.

Actually, I just dug it up; here you go. Skip to page 159. https://iowabirds.org/Library/Journals/2010-2019%20Vol.%2080-89/2016-Vol%2086/IBL-86-4.pdf

Super happy to have found this site!!

Martin, I can’t wait to check out the page you linked! Wow, so interesting that it wasn’t the Scarlet Tanager. I even found a website, years back when I first researched this, that had the birdsong and the violin’s melodic line side by side. LOL; guess I was gullible.

I love all of Dvorak’s quartets — it seems to me they’re underrated. They all are so beautifully melodic. I keep hoping I’ll develop a taste for Bartok’s extensive quartet works, which seem to be more commonly performed, but it’s just not happening yet. I guess they are two wildly different styles and can’t be easily compared.

Thanks for stopping by my site, and great to read your comments!