There is something about going to the symphony in the summer that makes it feel like such a different experience from its wintertime counterpart. How strange to enter Davies Symphony Hall while it’s still light outside. Inside, you stand at any of the building’s floor-to-ceiling windows—in truth, one entire side of the building is almost all glass—and you gaze out on busy Van Ness Avenue, drink in the sight of San Francisco’s gorgeous domed City Hall, the people, the hills to the west, the noiseless traffic below, and you bask in the San Francisco-ness of the whole scene, as golden sun from the west-facing windows floods the second-level open space.

Michael Tilson Thomas had been scheduled to conduct the June 20-22 program, which included a composition of his own, along with a co-commissioned new work by Steve Reich, and Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2, featuring pianist Yefim Bronfman. Alas, Tilson Thomas had to back out in advance of a scheduled cardiac procedure* and so guest conductor Joshua Gersen took the podium, replacing MTT’s composition with Arvo Pärt’s “Fratres for Strings and Percussion.” My ballet readers might nod wisely at this composer’s name; his “Spiegel am Spiegel” is the music to which Christopher Wheeldon’s ballet, “After the Rain,” is set. Both music and dance are stunning, unforgettable. Scroll to the bottom of this blog to watch what I mean.

Saturday night’s program promised a lot and delivered on every level. Yefim Bronfman gave a stunning, decisive virtuoso performance in Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2. Steve Reich’s new “Music for Ensemble and Orchestra” was lively, full of musical intricacies, fun to listen to, offering enough “new” to the classical music equation without sacrificing melodic flow. It can be hit and miss for new works in the classical world; this one was a winner. Alexander Borodin’s “Polovtsian Dances” provided an elegant, lyrical finish to the evening’s program. But ultimately, it was the first piece of the night, a simple (but not really) nine-minute composition that has stayed with me.

It was Arvo Pärt’s “Fratres for Strings and Percussion.” In his early career, the Estonian composer (b. 1935) was associated with modernist, avant-garde and twelve-tone compositions. In addition to composing, he worked for Estonian Radio from 1957 until 1967 as a sound director. At the end of the ‘60’s, he abruptly paused his compositional work in order to study medieval and Renaissance music. Early chants and Renaissance polyphony fascinated him. Around this same time, he also converted to the Russian Orthodox faith. When he returned to composing, in 1976, he was a different composer entirely. Eschewing complex atonality, he now combined elements of early sacred music, with economy and space. He created an entirely new tonal technique that he called “tintinnabuli,” which refers to bell-like resonances, conveyed by orchestral, chamber or choral groupings.

Here is a quote from Pärt himself:

I work with very few elements – with one voice, with two voices. I build with the most primitive materials – with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I call it tintinnabulation.

Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers – in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning. The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it?

It’s no wonder I so loved “Fratres for Strings and Percussion.” Pärt’s spirituality, his philosophy, is there, tucked invisibly into the music. I am, at heart, a contemplative, a spiritual seeker, a philosopher. “Fratres” was a match made in heaven for me.

I was sitting in Davies Hall’s Side Terrace section, adjacent to and above the musicians, not my usual seat, and it was a treat to be so close. The piece opens so very quietly. A percussionist beats out a low tattoo with something clacky (forgive my lack of orchestra lexicon) in one hand and more softly on a bass drum with the other, a passage he will return to over and over, as the melody line with its tintinnabulation cycles through the composition nine times. The strings enter, quietly. I found myself leaning in to catch every bit of the sound, eyeing the musicians to see who was actually playing, because initially it was just a few violins, yet I sensed there was a low drone going on as well (the cellos? The double basses?), so subtle that it created a mood more than a sound.

The piece grew incrementally in volume, bringing with it a soft, unspoken urgency. There seemed to be all sorts of emotions simmering just below the surface. Dense, big, life-and-death emotions. Ancient spirituality. None of it ever spilled out and rendered the work sentimental, or even fully definable. Like spirituality itself, the answers didn’t announce themselves easily.

Midway, the volume peaked, and reversed its journey back to growing quieter and quieter. All of it affects you at such a gut level. It’s majestic. It’s minimalist. It’s spooky and spiritual at the same time, and enormously nourishing if you’re one of those, like myself, who relishes silence between notes, and a message that delivers almost subliminally.

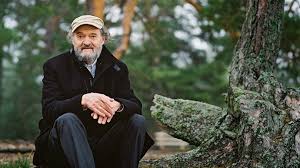

I think it’s time you give it a listen. And do you agree with me that the image/painting here could not have been more perfect?

The Soviets weren’t big into music that had any sort of religious or spiritual undertones. Estonia had been absorbed into the Soviet Union, so Pärt and his wife asked and received permission to emigrate to Israel in 1979. But plans were diverted en route when, on layover in Vienna, he received an invitation to record and publish his music in the West. He and his wife opted to settle in Berlin, where they have stayed, and there, he found great success.

Alex Ross shares the following in his book, The Rest is Noise:

“When the German label ECM began issuing recordings of Pärt’s music in the eighties, they sold copies into the millions, unheard-of quantities for new music. It is not hard to guess why Pärt and several like-minded composers achieved a degree of mass appeal during the global economic booms of the eighties and nineties; they provided oases of repose in a technologically oversaturated culture. For some, Pärt’s strange spiritual purity filled a more desperate need; a nurse in a hospital ward in New York regularly played Tabula Rasa for young men who were dying of AIDS, and in their last days they asked to hear it again and again.”

I can’t think of any higher compliment a spiritual-minded composer could receive.

If you’re thinking you’ve heard this haunting music somewhere before, you quite possibly have. Following is a list of films the music has been featured in. And to add further intrigue to the situation, there are over sixteen different arrangements of “Fratres” set for, among others, a wind octet and percussion; eight cellos; a string quartet; violin and piano.

- 1987 film Rachel River

- 1996 film Mother Night performed by Tasmin Little (violin) and Martin Roscoe (piano)

- 1997 German film Winter Sleepers

- 2006 autobiographical film La Morte Rouge directed by Victor Erice

- 2007 film There Will Be Blood directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

- 2013 film To the Wonder directed by Terrence Malick

- 2013 film The Place Beyond the Pines directed by Derek Cianfrance

- 2013 film Violette directed by Martin Provost

- 2015 film El Club directed by Pablo Larraín

- 2017 documentary film Mountain directed by Jennifer Peedom

And now, as promised, here is an excerpt of Christopher Wheeldon’s “After the Rain,” set to Arvo Pärt’s “Spiegel am Spiegel,” performed by New York City Ballet dancers (Wendy Whelen – anyone know who her partner is?)

*Happy to report that MTT’s cardiac procedure went well. According to a SFS spokesperson, he’s recovering well, the doctors called the procedure “a complete success” and that “his heart is performing at 100 percent”, and he’s right on track to return to the San Francisco Symphony in September for the 2019-2020 season, his—sniff, sniff—last with the symphony, a loss made bearable only by the über-exciting news this past year that Esa-Pekka Salonen would be replacing him as music director.

I just now read this. It was incredible. I have never before heard this piece, or even heard of it.

I especially liked this part:

“The piece grew incrementally in volume, bringing with it a soft, unspoken urgency. There seemed to be all sorts of emotions simmering just below the surface. Dense, big, life-and-death emotions. Ancient spirituality. None of it ever spilled out and rendered the work sentimental, or even fully definable. Like spirituality itself, the answers didn’t announce themselves easily.”

Thank you so much for your comment here, S. Markham, and glad you liked the post. I like the part you quoted, too. I slowed down to reread it just now and loved the way it inspired me (to write as good as that again!).