Today The Classical Girl gets to focus on a different subject, one equally near and dear to her heart. Food, food food. Now, if you’ve just joined me here, it might be because you clicked over from the “what do ballet dancers eat?” post. [BTW, If you came here through a link about mother-daughter relationships, read on – I get to that, too!] People love the “what do ballet dancers eat?” post. They’re flocking to it. I love that people love that post. The next best thing to eating food is thinking/talking/writing about it. So. When Jen over at The Ajennda invited me to guest blog about “5 Things,” anything I wanted, well, choosing the subject wasn’t a difficult decision. You can read my 5 Things over here http://www.theajennda.com/2014/05/5-things-foodie-things-edition-guest.html. My five foodie digressions, for the record, are 1) Classical Girl’s signature grilled cheese sandwich; 2) beef stock; 3) steel-cut oatmeal for dinner (yes!); 4) yummy luxury nuts and fruits; and 5) chocolate, because that is one of life’s most important subjects to ponder. I’m thinking one day chocolate will need to be its own blog. It’s that big in my world.

So, check The Ajennda out, check out my blog on “what do ballet dancers eat” if you haven’t been over there already. It’s got tips on how to eat/live like a ballet dancer, or simply eat/live like someone on a healthy diet who loves their body and wants to enjoy food and life. And I’m hoping that covers most of us. https://www.theclassicalgirl.com/ballet-dancers-eat/

Now for the mother-daughter relationship reference. I’m going to use this opportunity to share an essay that appeared in Women Who Eat: A New Generation on the Glory of Food (Seal Press, Nov 2003). It’s particularly fitting for two reasons. First of all, it’s about food, food, food. Second, it weaves food in with the concept of family, namely my mother. As Mother’s Day approaches, thoughts always shift that direction. For those of us who’ve lost our mother, stories about our moms become particularly poignant. So. Indulge me, please, as I digress about food, and my complicated (aren’t they always?) relationship with my dear mom. And there are two nifty recipes at the end: Mom’s egg casserole and Terez’s African Egg Casserole. All the more reason to give it a peek, huh?

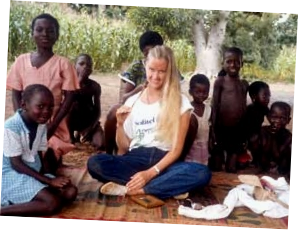

“LESSONS FROM GABON”

I’ll never make fun of your meatloaf again, Mom. Just get me back to sample some. Five days into my two-year Peace Corps assignment in Gabon, Central Africa, I was ready to go home. Baked chicken, buttery garlic bread, green bean casserole, mashed potatoes and gravy . . . The thought of all I’d taken for granted plunged my diarrhea-ravaged stomach into further misery, as I stared at my plate of rice and mystery meat drowning in fiery sauce. I would even settle for your Friday night fish sticks and tater tots, Mom.

I grew up in the Midwest at the tail end of the Boomer era, under the motherly influence of Mrs. Paul, Mrs. Smith, Ore-Ida, and the Swansons. They were like family, benevolent aunts always there to assist my mother in her endless, nightly role of feeding eight children. She was old-school, staying at home to raise her oversized brood, but without nearby extended family to help. My father was not unsympathetic to her plight. Instead of building a mother-in-law unit, he built a small room to house my mother’s greatest support system: the freezer. A big one.

My mother had no time to peruse creative recipes or experiment in the kitchen. There were always dishes to wash, noses to wipe, fingerprint smudges to clean, arguments to break up, crying kids to hug. Every frozen or canned shortcut found a place in her kitchen. A meal of tater tots, broccoli, fish sticks, and Cling peaches in syrup could be on the table in twenty minutes, leaving more time to fold laundry, vacuum, and herd little ones to bed. And yet, she managed to incorporate a few old-fashioned meals into our weekly repertoire, like Sunday roasts with onions in the gravy; thick, meaty spaghetti sauce with fragrant garlic bread on the side; casseroles that bubbled with cream and tangy cheese–never mind that the vegetables on the side were always canned or frozen and we had sandwich cookies for dessert.

I didn’t think twice about leaving it all behind to join the Peace Corps in 1985. What twenty-two-year-old does? I was ready for a grand adventure, far beyond the confines of family and Kansas.

**

I learned Africa’s first lesson quickly: eat to live, instead of living to eat. Food here was a necessity—not an indulgence, or a source of guilty pleasure. Gabon’s main staples were rice and manioc, an indigenous tuber that is boiled, pounded, boiled again, pummeled, kneaded, then rolled into a banana leaf to form a baton of pale, stiff, nearly tasteless goop, visually reminiscent of the translucent pink erasers used by grade-school kids. One of these starches, accompanied by a ubiquitous, spicy tomato sauce, usually with some form of protein bobbing about (smoked fish, monkey, river rat in the village; beef, chicken, or fish in the cities), is what the average Gabonese eats. During my three-month training, it is what I ate too.

Culture shock and fear of the unknown produced a sick weepiness in me that made me want to stuff creamy casseroles into my body, wolf down burgers and fries, meals all unavailable here. To not have access to familiar foods was one of the worst feelings I’d experienced in my easy life. Food, I realized, had been my most loyal friend. It had sustained me through breakups and periods of angst, depression, boredom. It was something I could control and manipulate. Salt. Fat. Cheese. My pulse would quicken at the thought of the next meal. In Gabon, I didn’t know what the next challenge would be or how I’d solve it. Now, when I needed comfort more than ever, my old friend had fled–to be replaced by monkey and manioc.

**

After three months of Peace Corps training I received my teaching post, along with my own house. Amid continued homesickness, preparing my own food helped connect me once again to family, to control. In the kitchen that first night, I made canned corned beef and onions over rice. By normal culinary standards it was pretty forgettable, but the familiarity, the warmth of the food, comforted my heart as well as my stomach. It was canned. It was processed and salty, not spicy. It could have come from Mom’s kitchen.

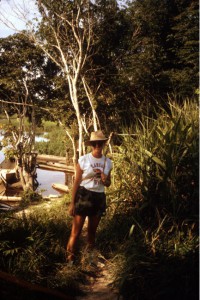

In Makokou, a provincial town of 6,000 surrounded on all sides by emerald rainforest, I struggled to acclimate. I still relentlessly craved the honest, predictable comfort of Mom’s cream of mushroom soup-based creations (cream of mushroom soup being the key ingredient in any self-respecting Midwestern cook’s arsenal). As I ate corned beef and rice, bland fish and rice, spaghetti and rice, I dreamed of tuna noodle casserole, scalloped potatoes, green bean casserole with canned french-fried onions on top. In one sense, I was a fortunate Volunteer–I had an oven in my galley-sized kitchen, and a few battered pans. But there could be no casserole without Campbell’s, which the local store shelves conspicuously lacked. Baked chicken, then, I thought. Another roadblock–in the provinces, chicken was hard to find and expensive. I found turkey wings, however, which I promptly baked Mom-style, dipped in flour and spices and basted with butter. When the familiar garlicky, rich smell of cooking poultry began to permeate the house, I almost wept with relief and nostalgia.

**

Although I loved my mother dearly, we never had that much in common. Her quiet, compliant nature paled against my flamboyant theatrics. Always warm and loving, she was emotionally elusive. She never confided in us and I never once saw her cry. Was this a result of her upbringing? A generational difference? Or did thirty years of raising nine kids, burying one as an infant, simply beat any subversive emotion out of her? The older I got, the more I wanted to know. I pestered her over dinner preparation. Did it make her nostalgic to prepare Swiss steak, one of the few recipes from her mother’s kitchen? What were her childhood dinners like?

“Does the thought of cooking these same meals, day after day, ever make you want to freak out?” I tried once. “Don’t you want to kick up your heels occasionally and try something wild and new?”

“…Honey, I don’t know,” she’d say with a puzzled smile. And that’s all I got. How frustrating her responses were to someone like me, whose nature it was to dig relentlessly until I found answers.

That’s how I approached food too. I’ve always hungered to know why foods as basic as sugar cookies can vary so much by rendition, why some hollandaise sauces taste bland and heavy, while others are so exquisite, ethereal and buttery. What was the secret of good food? With time on my hands in Gabon, I pored over the Betty Crocker cookbook Mom sent me. I compared recipes. I attempted new dishes Mom had never made. Quiche. Fritters. Paella. Chicken tetrazzini. Sometimes I’d leaf through the cookbook and peruse recipes I didn’t have the ingredients for: Oriental veal casserole (a rather frightening concept, incomprehensibly requiring cream of mushroom soup). Shrimp rémoulade. Nesselrode pie. (To this day, I don’t have a clue what or who or where “Nesselrode” is.) Pumpkin pie. On this last one, homesickness in November provided a powerful motivator to find substitutes for absent ingredients. I plucked a green papaya from a tree in my yard. Boiling and mashing it, I mixed it with evaporated milk, egg, sugar and spices. Trial and error finally produced the best pumpkin pie substitute in Central Africa. Mrs. Smith would have begged for the recipe.

During meals with friends featuring African food, I spent long moments in meditative silence, trying to define the flavors, to discern what made them so different from the foods I’d eaten growing up. The answer: peanut butter and lots of oil. Also piment, a chili pepper similar in heat to a habañero that lifted the blandness of rice and tomato sauce. The flavors that had evoked uneasiness upon my arrival now began to intrigue me.

**

I encountered many roadblocks to my experiments, which pretty much defines life in Africa. The thermostat in my oven was broken. There were no frozen amenities in the local store, only lumpy, ice-crusted packages I learned to identify as turkey wings and on a good week, beef chunks and an occasional whole chicken. I had to make rice the old-fashioned way. It shocked me to discover how long it took, after the convenience of Minute Rice. It tasted better too, once it stopped sticking to the pan. Bit by bit, I modified American recipes with what was available and learned through experience how to gauge my oven temperature: I’d stick my head close, letting my face get the full blast of the heat. A 400-degree Fahrenheit oven blasts the face in a quick wave, so that loose tendrils of hair wave back in retreat. A 375° oven is softer, more like an ocean swell. 450° is like a slap. Any higher, the eyebrows singe.

Spending time in the kitchen connected me to Mom. I saw more clearly how her personality manifested itself in her plain but comforting food, honestly and lovingly prepared. She found help where she could, quietly bearing the burden of cooking for a big family every night for over thirty-five years. I imagine her mother did the same. As I experimented in the kitchen, a benevolent spirit filled the air, the ghosts of my matrilineal ancestry, generations of women who have all used the available food to create a sense of home and family, compromising when need be. My mother left security and extended family behind when she moved 500 miles with her husband and six (soon to be seven) children. Her grandmother was torn from her German homeland. I’m certain she struggled with the unavailability of familiar kitchen staples just as I did in Gabon. We all learned to adapt and thrive.

The first year was the hardest. I wrote Mom asking for suggestions and she sent me some of her powdered shortcuts: Dream Whip instant whipping cream, Lipton’s onion soup mix, ground spices, dried cheese sauce. She mailed little packets of French’s yellow mustard with a notes about how the crew at the local McDonald’s probably called her “that crazy lady who always asks for one hamburger and six packets of mustard.” I’d never heard her crack a joke or confide before–she was a different person on paper.

And then she sent the egg casserole recipe, the only casserole in her repertoire that didn’t require cream of mushroom soup. In my hometown neighborhood, egg casserole was synonymous with celebration. Someone always brought it to brunches, to go with the muffins, bloody marys and screwdrivers. The dish was rich, oily, tangy, and substantial, with loads of cheddar cheese and pork sausage. My mother always made it for holiday breakfasts.

When I received the recipe, my heart leapt as I gazed at the index card with Mom’s careful, familiar handwriting. Home, it whispered. I’d brought cheese back from the capital city of Libreville, but in regards to the pork sausage, modifications were once again necessary. I fried canned corned beef (it was either that or turkey wings) in a pan with plenty of oil until the gooey rose-colored mush separated a bit and grew crispy. In place of Tabasco, I used piment, so hot you need to chop it with protected hands or else you’d suffer its burn for days (recognize the voice of experience speaking here). Having combined the fiery bits with oil, I now added a few drops to the meat. I mixed in eggs, milk, the hoarded cheese, mustard and bread, refrigerated it overnight and popped it in the oven on Sunday morning. The rich, buttery smell coming from the oven an hour later invaded my senses like a drug.

When I sat down and tasted the concoction, the flavors leapt out at me. I shut my eyes and let the cheesy richness transport me home, to the oversized dining table that sat twelve, to the adjacent gold and green print drapes that didn’t quite match the industrial carpet beneath. To Mom, Dad, my seven siblings and their children in highchairs who banged spoons on trays, everyone raising their voices in order to be heard over the cheerful din. I opened my eyes to find Africa, where unknown trials awaited me. Parasites and insects were sure to compromise my health. Would thieves yet again break into my un-secure house? But at that moment, I had my egg casserole. I took another bite and smiled.

**

Somewhere during my second year in Gabon, I went from simply accepting my culinary compromises to enjoying them. Like the locals, I regularly doused the plain food I made with piment, savoring the burn that made my eyes water and nose run. I learned to prepare fresh fish and other can-less meals. I snatched up avocados, mangos, guavas, and passion fruit–items I’d never used or even seen at home–whenever they appeared at the local market. On a daily basis I visited the local boulangerie, which produced surprisingly excellent baguettes.

Libreville, the capital city, hosted thousands of French expatriates. The French firmly embraced the “live to eat” philosophy, and no hardship post in Central Africa was going to keep them from living it. Stores catered to their tastes, providing olives; pâte de fois gras; tiny, tart cornichons—all new to my Midwestern palate. The cheeses alone were an education. (Back home, cheese meant Velveeta. My mom used to wave a cheese cutter through the orange loaf. She called her creation “nervous cheese,” because of the squiggle shape, and served it as a side dish.) In Libreville, I discovered grating cheeses, semisoft cheeses, baking cheeses, unbelievably foul-smelling cheeses. Like all Volunteers, I learned to stock up on cheese, chocolate, and other French goodies whenever I visited.

Africa’s more relaxed pace, combined with the French eating philosophy, produced long, lazy dinners with friends. Lingering over wine after plates were cleared, we argued about reincarnation, what made a good croissant, Western policy on developing nations, and why Regab, the Gabonese national beer, kicked Budweiser’s ass. Candles, a necessary preventative measure for the frequent power outages, lit the animated faces around the table. As I brought out Pont l’Évêque cheese and sliced mangoes for dessert, a voice whispered, “You don’t need to long for home anymore. You are home.”

**

And then it was time to leave my new life behind and return to Kansas. I wasn’t prepared for the reverse culture shock. Without the piment I’d gotten used to, Midwestern food seemed staid and lifeless. Mom’s spaghetti sauce wasn’t as satisfying, maybe because I’d learned that aged Parmigiano Reggiano cheese worked better on top than Borden’s grated domestic Parmesan (“New and improved, longer shelf life!”). Back to Minute Rice, frozen vegetables, tater tots, and fish sticks. Popping biscuits out of a can seemed absurd, almost surreal. My two-year absence had served to show me, with painful clarity, mainstream Midwestern America of the ’70s (Mom never really graduated to the ’80s).

I tried to introduce the “new me” to the family. One night I made paella, accompanied by garden-fresh greens and avocados tossed with homemade vinaigrette. I’d procured crispy French baguettes. I lit candles. My dad tried to leave the table after shoveling down a plateful. I told him he had to stay for dessert. We needed to linger, drink coffee and argue philosophy.

“Cheese for dessert?” my father spluttered when I brought Brie and grapes to the table.

“It’s not orange,” my sister complained. I grabbed a bag of Hershey’s Kisses Mom kept around and bribed everyone to stay fifteen minutes longer. At our Midwestern table, that was the best I would get.

Kansas betrayed me–or did I betray Kansas? Regardless, I had one consolation prize: my relationship with my mother had improved, now that we had cooking in common. She was happy to relinquish partial control of the kitchen as I continued to prepare side dishes more in line with my new tastes. As we puttered in the kitchen, she’d listen with rapt attention to my Africa stories, especially the ones detailing my kitchen disasters. (Dropping a full pot of spaghetti on the floor, seconds before serving it to a group, and serving it anyway; running out of propane for the oven midway through dinner party preparation; setting bread on fire, to name but a few.) Mom alone never tired of hearing them. My trick of successfully guessing the oven’s temperature using my face endlessly entertained her. She loyally ate seconds when I made the family my African-style egg casserole, with corned beef and lots of Tabasco. (Corned beef, it turns out, is a poor substitute for pork sausage.) I’m sure my passionate nature baffled her, but I saw her girlish appreciation of the way I still insisted on candles at dinner and made Dad stay at the table longer. She wouldn’t have done it on her own.

I tried once to branch away from our safe culinary conversations to ask her again if her never-ending job in the kitchen stifled a more creative, idealistic side of her. She gave me the same puzzled smile she always had and said, “Honey, I just don’t think that way.” I suppose that’s one step up from saying, “Honey, I don’t know.” It eventually sank in. She wasn’t introspective–in her era, that could be a dangerous thing. And I was; I could afford to be. We would always be two different women from two different generations.

**

It’s been fifteen years since my return from Africa and twelve years since my mother died in her sleep, slipping away as uncomplainingly as she lived her life. I have few souvenirs of her–she wasn’t a woman who believed in material possessions, sentimental knickknacks. For that reason, the egg casserole recipe card stands as one of my most precious mementos. Stained, dog-eared, and yellowing with age, Mom’s elegant handwriting gracing the card, the recipe evokes memories of my youth, my struggles to adapt in a foreign place. It also represents the only casserole that made it into my adult repertoire, surviving the purge of my Midwestern palate.

Like the French, I live to eat, celebrating life through food. However, I don’t prepare what my mother and her generation produced. Early on, I sent Mrs. Paul, Mrs. Smith, and Ore-Ida packing. Tater tots, I told myself, along with canned biscuits and frozen broccoli, would never appear on my table. I’ve got many like-minded friends here in Northern California and we laugh together about surviving childhoods full of cream of mushroom soup and frozen atrocities. But surely my mother is up there laughing now as my young son rejects my organic, seasonal creations in favor of what really interests him: frozen food. Chicken nuggets, hot dogs, frozen pizza–that’s all he wants. Ore-Ida and the gang now get visitation rights. Once again, I yield, I compromise, and it makes life easier. “Now you’re getting it,” Mom tells me.

MOM’S EGG CASSEROLE

- 1 pound of bulk pork sausage, diced, browned and drained

- 6 slices of white sandwich bread, cut into squares (no crusts)

- 2 cups milk

- 4 eggs, beaten

- Dash of Tabasco

- 1 teaspoon dry mustard

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 pound grated Velveeta or cheddar cheese

Mix all ingredients, pour into 8×8 pan and refrigerate overnight or twelve hours. Bake at 325 degrees for one hour. Cover with foil before baking. Last fifteen minutes, remove foil. Casserole is done when center has set. Cool slightly and enjoy.

TEREZ’S AFRICAN EGG CASSEROLE

- 1 can corned beef

- 1/2 teaspoon piment-oil mixture

- 2 tablespoons peanut or palm oil

- 1 baguette, preferably not too stale

- 2 cups water

- 6 tablespoons powdered milk

- 4 eggs, beaten

- Two packets of McDonald’s prepared yellow mustard

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 Bonbel cheese, (in the red wax rind), chopped up

Fry corned beef in oil (palm oil will have a stronger taste, but if it’s all you have, it’s all you have), until mixture becomes less gooey and more crispy around edges. Break up into small pieces. When it vaguely resembles pork sausage, remove from heat and drain. Sprinkle piment-oil on top. Mix water with powdered milk, whisking out lumps. Take baguette and pluck out all the fluffy white stuff, leaving crust behind. (Save to slather with peanut butter for next meal.) Mix all ingredients and pour into any pan available and just make it work. Refrigerate overnight, assuming you have a refrigerator. Next day, preheat oven, testing by holding face over open door. If heat blasts and is intensely uncomfortable, turn it down. If it’s slow to hit face and feels more like hot New York sidewalk in August, turn it up. Stick cookie sheet on top of pan for the first 45 minutes since no aluminum foil available in entire town. When incredibly good smell wafts out of kitchen, reminiscent of home, check casserole. If burnt, too bad, live with it. If only half-cooked because your propane tank ran out midway and the town’s general store is out of propane until the following week, too bad, live with it. If it’s cooked and doesn’t jiggle in the middle, congratulate yourself and remove from oven. Cool slightly, if you have the patience, and enjoy.

Excerpted from Women Who Eat: A New Generation on the Glory of Food (Seal Press, Nov 2003) http://www.amazon.com/Women-Who-Eat-Generation-Glory/dp/1580050921/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1399132550&sr=8-1&keywords=women+who+eat

Great timing sis— one of my favorites! I guess your soup with spinach lunch didn’t make the top five

Kathleen, it did, sorta, on The Ajennda post. I mentioned my quirky thing of only eating a half sandwich and always with a cup of soup, and mentioned that pea soup was my fave. I’d originally nattered on about how I like to steam two fistfuls of spinach in chicken broth and then add 2/3 cup of pea soup, but that was making the essay drag on. But oh, totally, that’s on my top 10 list.

Hmmm– my reply was cut off….

Also want to recognize that both my relationships to my mother and to food are complicated. Are these two things related?

I love it when your reply gets cut off and you have to reply twice because it makes my post seem really popular. ; ) And I like your comment here – what a great thing to ponder, the relationship to food in tandem with the relationship to one’s mother. Ooh, it would be fun if someone else chimed in to voice their opinion there…

What a fantastic entry! It truly transported me to both your Mom’s Kansas kitchen and to your own makeshift one in Gabon. Mom and daughter relationships can be difficult, but equally, loving and rewarding and you’ve captured that so well. You write beautifully. Thank you for sharing.

Marie, I was thrilled by your comment – thank you so much! It’s such a long entry for a blog, and my thought was, oh, no one outside family and friends will bother to read it all. Soooooo glad you did, so glad you enjoyed it, and so glad you took the time to comment! Thank you – your words are warming my heart. : )

This reminds me of my grandmother. She was a cook and she also taught cooking. She had cancer, and when it became clear she would not survive, she wrote down all her favourite recipes on little cards. My sister and I still use them.

Paulina, my first question, since I am such a foodie, is…. oooh, what are the recipes? Were the dishes memorable? Will you share the recipes?

I don’t know if you happened to read my other blog, on “Gentle tips for the motherless daughter on Mother’s Day,” but I actually took a photo of the original egg casserole recipe card and posted it on my blog. Handwritten recipe cards are pretty astonishing things. I’m envious that you have some – and multiple! – from two generations back. So very cool.

Thanks for sharing your story!

Terez – I’ve been reading some of your blogs just now, finishing with this essay. Brings back my own memories of when you were in Africa (remember the letter to Dusky?), and of life in the Midwest, including my own complicated relationship with mom. Your anthology essay was and remains so evocative of that time and space. I loved rereading it, and it gives me a renewed appreciation for your culinary adventures and gift of writing.

Annette, I loved your comment, and I loved that you commented. Thank you! Dang, what an interesting perspective it would be to read your own essay on that very same time. Um, write, please? And share?

Namaste!!

Brought me “home” to my kitchen in Tchibanga (83-85) and I cried. Gabon d’abord…

Oh, what a wonderful comment to read! Such a powerful uniter, hearing someone else has served in Gabon, and so close to my years (85-87). Thanks so much for sharing this, Mbouroubou – I feel all the warmer for it.