It was a night for music lovers, not just ballet lovers, last Saturday at the San Francisco Ballet. Beethoven’s Piano Trio no. 1, Saint Saens’ Symphony no. 2 (injected with the sublime 2nd movement from his Symphony no. 3) and Stravinsky’s iconic The Rite of Spring. We are so fortunate, we of the San Francisco Bay Area, to have such quality music performances available, and not just from the Symphony across the street. Music director Martin West and the San Francisco Ballet Orchestra did a knock-up job Saturday night. The Rite of Spring, in particular, was astonishing.

The night’s dancing, too, was sublime. There was Mark Morris’ Maelstrom, twenty years after its premiere, the first of eight ballets the San Francisco Ballet has commissioned from him. Caprice, a world premiere this season from SFB artistic director Helgi Tomasson. Yuri Possokhov’s The Rite of Spring, a reprise from last year’s premiere that itself commemorated the centennial of the ballet’s first turbulent, riot-provoking Paris debut. Great stuff.

More about the opener, Mark Morris’ Maelstrom. Morris’s choreography is widely acclaimed for its musicality, craftsmanship and ingenuity. More of a modern choreographer at heart, he likes to push the boundaries on what constitutes classical movement. The result is neoclassicism tinted with modern, a flexed foot or hand thrown in, a pause in an inelegant position. Twenty years after its premiere, the ballet still looks fresh and interesting. The dancing felt rather busy in the first movement, however, with small groups of dancers repeating the same combinations, only some a few counts behind, producing a quasi-confused swirl of syncopated (and sometimes not) dancers, which I guess is a good definition of a maelstrom as well. The cast was a fourteen member ensemble. It was hard for me to follow which dancer was which. (Notable, in spite of this, were Sarah Van Patten and Sasha de Sola.) But it’s to the corps de ballet dancers’ credit that, often, I couldn’t even discern rank. Bravo (bravi?) to dancers Shannon Rugani, Steven Morse, Julia Rowe, Lee Alexandra Meyer-Lorey, Jeremy Rucker, Wei Wang. You all looked great amid your higher ranked peers.

© Erik Tomasson

A musical treat: a live piano trio, just off stage right, in the pit. Musicians—violinist Kay Stern, cellist Eric Sung, Roy Bogas on the piano—did a wonderful job. Beethoven’s Piano Trio no. 1 is nicknamed the “Ghost” trio for the ghostly beauty of second movement. It all worked so well, music and dancers and musicians.

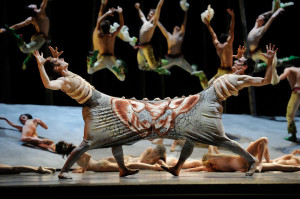

Hopping ahead to Possokhov’s The Rite of Spring, last year’s premiere celebrating the centennial of the 1913 Ballets Russes production, deemed so unorthodox it incited riots outside its Paris theater. Stravinsky’s music, created for the ballet, (choreographed by Nijinsky for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes), is extravagant, compelling, a mammoth of a score, at turns chaotic, sensual, gleeful, and terrifyingly remorseless.

© Erik Tomasson

Possokhov has nailed the mood, the original ballet’s intention. Based on Russian folklore, The Rite of Spring depicts a primal culture, relishing the arrival of spring and sensuality. Lights rise on a woodland set, a hillside incline, designed by Benjamin Pierce. Sleepy young women awaken, roll down it, and stand to greet the spring day, embracing it as well as their own sensuality (dresses slowly pulled up, over their heads, revealing their gorgeous young bodies, the ultimate symbol of fecundity). Young men join them, quivering and eager to embrace the spectacle (not to mention the girls). Ah, spring. But there’s a price to pay. A young woman, “the chosen,” must be sacrificed to appease the gods, so the others might live. The sensual, feral nature of the ballet, the choreography, was engrossing to watch last year, and even more enjoyable this time. Jennifer Stahl, as the chosen one, nailed the role for the second year in a row, and now officially owns it, as do the deliciously fearful pair of conjoined elders (sharing the same skirted costume) James Sofranko and Benjamin Stewart, spears in hand, who carry out the dictate. And kudos to Luke Ingham, the chosen one’s consort, his second big role for the night, following Caprice. Busy night for Ingham. Lots of lifting. Well done.

Sandwiched between these two ballets was Helgi Tomasson’s world premiere, Caprice, which featured nineteen dancers, including two pas de deux couples. A shifting backdrop designed by Alexander V. Nichols was mesmerizing: lit beams, like pillars intersected by one horizontal beam, all of which moved closer/further between movements, creating a different mood each time. Wonderfully effective. Costumes, designed by Holly Hynes, were flowing and lovely, the two principal women in paler colors than their ensemble counterparts. “Flowing and lovely” describes the neoclassical choreography as well. Lyrical, easy on the eye, no great risks, no pushing at the boundaries.

© Erik Tomasson

Principals Maria Kochetkova, Davit Karapetyan and Yuan Yuan Tan rank among the company’s top dancers, and they all were in fine form. Tan, skillfully partnered by Luke Ingham, had her signature liquid elegance, those distinctive long limbs and feet and airy lyricism. In the second movement, she was slid along on the floor by Steven Morse and Hansuke Yamamoto (and Luke Ingham?) and it was so playful, so deliciously smooth and quick-moving, like watching a nice sailboat skim across the San Francisco Bay on a sunny day.

Davit Karapetyan, too, was a powerhouse that night. Is it just me or is he suddenly magnificent this season? There’s an authority, a power to his jumps, his upper body presentation made him thrilling to watch. Kochetkova, his partner, was wonderful; she always is. I don’t think I’ve ever seen her paired up right next to Tan, though. This ballet allows for a study in contrasts from these two very popular, beloved principals. The third movement, in particular, where the music shifts from Saint Saens’ Symphony no. 2 to the second movement his Symphony no. 3 gives us an unprecedented opportunity to watch not just one but two pas de deux lead couples sharing the adagio movement.

I’ve long been in love with this movement/symphony ( https://www.theclassicalgirl.com/haunted-by-saint-saens-organ-symphony/ ) which gave this shared pas de deux Peak Moment Status for me. Honestly, I can’t wax lyrically enough about it. The music, and the dance, transported me.

The last minute of the movement has the two pas de deux couples alternating overhead grand jeté lifts, moving from one side of the stage to the other. Lighting (by Christopher Dennis) was perfect. Both the movement and the music were gorgeous, dreamy. A six-note descent motif offers first the woodwinds. The violins repeat. There’s almost a searching motif, the first voice on a quest, the lower voice responding, a haunting counterpoint.

Take a listen for yourself, down below. The score traditionally calls for an organ (thus the symphony’s nickname, “The Organ Symphony”) but the SFB orchestra fared very well with a transcribed use of woodwind voices instead. The second movement starts around 10m29. The six-note descent section (think ethereal overhead grand-jeté lifts as you listen) is at 18m30.

No doubt about it, a night of great dance and music. Well done, San Francisco Ballet and SFB Orchestra both.

http://

PS: Looking for more recent and/or specific dance reviews? You can find all those links HERE